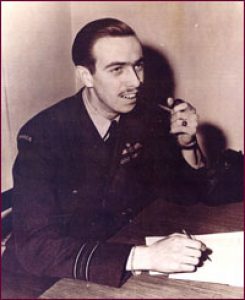

We remember: WWII Veteran and McMaster student Byron (Barney) Rawson

The life of Byron (Barney) Rawson was one of huge promise, cut short by the ravages of war.

The McMaster student would reach great heights as a decorated member of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) during World War II (WWII) but would meet a tragic end just three weeks after his 23rd birthday.

Rawson grew up in Ottawa but moved to Hamilton in 1922 when his father, a Methodist minister, was appointed to lead the Centenary United Church in the heart of the city’s downtown.

The teenager attended Westdale Secondary School until his graduation in the spring of 1940.

The young grad had dreams of being a lawyer or politician when he enrolled at McMaster University later that year. But those dreams would never be realized.

France had fallen to the Nazis that spring, and Great Britain was suffering under the unrelenting air raids carried out by the German air force the summer before Rawson arrived at McMaster.

The history student soon found his extracurricular time divided between sports teams and training in the McMaster Contingent of the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps (COTC), a unit that had been established when conflict first broke out.

Rawson was able to finish his first year at McMaster but would not return for his second.

A May 1941 communication from McMaster’s registrar acknowledges Rawson’s intentions to leave the school to enlist with a sign-off that reads “Alma Mater […] salutes you.”

The 18-year-old formally enlisted in the RCAF and was sent off to Quebec for training.

Soon the young pilot was flying in dozens of dangerous missions. He always managed to return home, though his comrades were not always so lucky.

Rawson would quickly climb the ranks and received many promotions during his service.

By the summer of 1943, he had been promoted Flight Lieutenant and had gained the reputation of a “pretty cool customer” in the words of a crewmate.

A high point in his career came that fall when he was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) by King George VI himself at Buckingham Palace. The DFC is awarded for an act or acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty performed while flying in active operations against the enemy.

The ceremony was attended by other members of the royal family, and Rawson, later recalling the event in a letter to his sister, wrote “Princess Elizabeth […] is far more attractive than her pictures.”

Rawson was only 21 when he was again promoted, this time to Acting Squadron Leader. His letters home around that time included jokes about growing a mustache for warmth, but family members believe it was more likely intended to hide his youthful features.

By the time Rawson flew his fifty-third and final mission in April 1945, he had been promoted once again, had a bar added to his DFC and was given the title of the ‘youngest Wing Commander in the British Empire.’

After the war ended, the newly returned veteran registered for law studies at Osgoode Hall in Toronto – admitted without the required admission criteria thanks to his military service.

While life seemed to be getting back on track for Rawson, he confessed to a childhood friend that he was suffering from insomnia and nightmares.

Rawson took his own life, just two days before Christmas. He had been home from the war for only three months.

Days later The Hamilton Spectator would attribute the young veteran’s death to “a complete nervous breakdown.”

Peter Jackson, Rawson’s nephew, later told the CBC his uncle was a religious man and the weight of dropping bombs during his service “would have been wrenching for him.”

While Rawson would likely be diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder by today’s standards, prevailing attitudes at the time derisively labelled war-related injuries as ‘battle fatigue’ or even ‘lack of moral fibre.’

The veteran’s grave in Hamilton’s Woodland Cemetery bore no mention of his service because Rawson was not considered “war dead,” something the Commonwealth War Graves Commission only righted decades later.

McMaster, for its part, felt Rawson’s sacrifice deserved recognition.

George Peel Gilmour, McMaster’s chancellor at the time, spearheaded a movement to have his name added to the honour roll tablet at Alumni Memorial Hall to pay tribute to the graduates and undergraduates who died in the war.

Rawson’s name has since stood alongside dozens of other students who also gave their lives in the gruesome conflict that saw over 45,000 Canadian soldiers killed.