Letters from the Past: Mac grad helps Canadians share family war stories

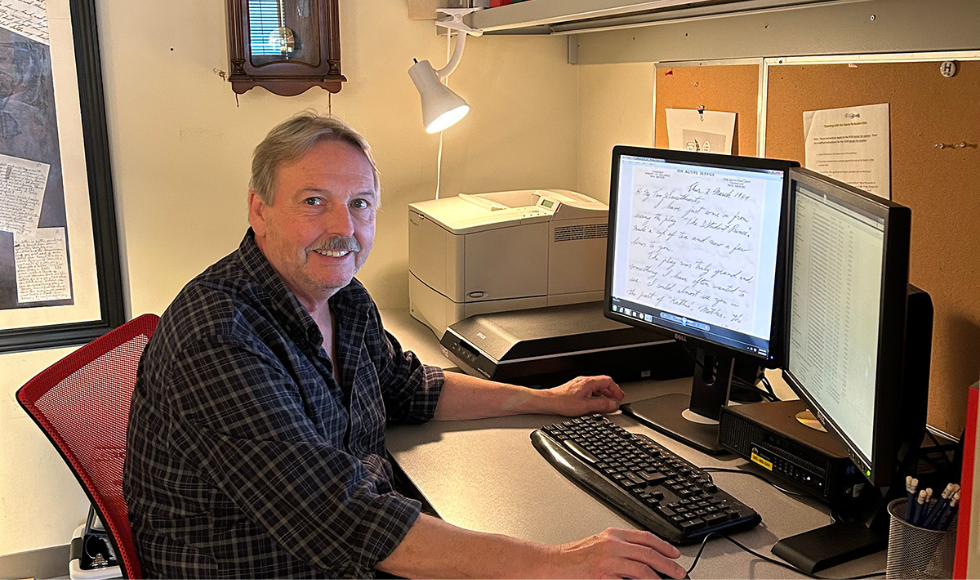

What started as a small project for historian and Mac grad Stephen Davies has grown into Canada's largest online archive of Canadian war materials.

Twenty-four years ago, McMaster graduate Stephen Davies was teaching a history class about World War I. While the dates, battles, names and statistics he cited were integral to his curriculum, Davies felt something was missing: He wanted his students to connect with the real faces, lives and people behind the numbers.

So he went searching for publicly available materials documenting real Canadian soldiers’ personal experiences of war — letters, photos, and diaries. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to be found.

“When I first started teaching, there was very little Canadian material,” Davies says.

He made it his mission to uncover these important stories from Canada’s history, aiming to collect around 200 letters to share with his students.

He never imagined that his small project would snowball into Canada’s largest online archive of Canadian war materials, with over 35,000 letters and thousands of photographs.

Now in its 24th year, The Canadian Letters and Images Project is host to thousands of letters from both the home and battlefront.

The materials come straight from the closets and attics of Canadians. Unlike museums or libraries, the archive temporarily borrows materials from families, digitizes them, then gives them back to their rightful owners. This process brings the documents into the public domain, where they can be used by students, researchers, and the general public.

A range of Canadian voices

“We’ve really struck a chord with Canadians,” Davies says. “Families are very proud of their ancestors— they want to share those stories, but they also want to hold on to those valued family heirlooms.”

Davies is especially proud of the range of voices represented in the letters — voices that go largely unheard in the larger retelling of Canadian war stories.

“We have the farm boy from Saskatchewan, whose story is just as important as the officer from Toronto,” he says.

“We have female voices as well, from the home front or in WW2 serving as Wrens or other armed forces.”

The documents give Canadians real and raw insight into what life was like during the war.

“This is not through a lens of interpretation,” says Davies, who serves as the Project Director and a full-time history professor at Vancouver Island University.

“It’s literally seeing the war through the eyes and the words of the participants.”

The pull of history

When Davies was a child, his father would take him on summer road trips and insist on stopping at every historical marker along the highway. His dad’s passion inspired Davies to study history at McMaster for his undergraduate degree.

Davies loved his time at McMaster and was particularly inspired by a second-year history professor, John Weaver. “I loved his teaching style and his research,” he says. “It was a natural fit.”

Davies didn’t set out to be a history teacher. He thought he’d “just get a job” after graduating in 1980 — something like selling insurance. He ended up following his curiosity and pursuing a master’s degree, again thinking he’d get a “real job” afterwards.

By the end of his master’s, “I just couldn’t pull myself away from the history,” he says. He also wasn’t done with McMaster.

The strong bond he’d formed with John Weaver brought him back to Mac for his PhD, which he obtained in 1988.

“One of the lessons I learned was that if I’m going to spend that much time studying, I really need to get along with somebody, and John and I always did well together. I deliberately came back to McMaster so I could work with him,” he says.

And it’s a good thing he did. Thanks to his dedication, the next generation now has access to a whole other dimension of war history – one that centers the human experience.

The human cost of war

“When I teach, one of the hardest things for students to understand is the human cost of war,” Davies says. “Particularly when we start to talk about battles with 10,000 – 20,000 casualties.”

Davies believes that letters are the most powerful source for recreating what we’ve lost in the war. “They add a dimension to the battles that students don’t think about,” he says.

Interestingly, in most of the letters, soldiers don’t speak much about the war at all, he says. They talk about seemingly benign topics like the weather, the local skating rink at home, or missing their mom’s cooking. The letters were an important form of escapism, Davies says, serving as a link to their past lives and their future hopes.

This Remembrance Day, Davies encourages people to reflect beyond just the names carved on cenotaphs. “These are more than numbers or statistics. Remember the human face and the loss that these names represent,” he says.

He encourages Canadians to read letters from real soldiers like Hart Leech, whose final letter to his mother showed “a remarkable sense of acceptance,” while still maintaining a sense of humour. Three days later, Leech was killed in battle. His mother didn’t receive the letter until 12 years later.

His story is just one of thousands that have been permanently preserved, thanks to Davies’ work.

Davies also encourages anyone who has letters, photos, diaries or personal materials from a loved one documenting the Canadian war experience, from any war, home front or battlefront, to contact the project.

“What you have is important,” he says. “Every letter is important, every photograph is important.