Archive shares remarkable story of Royal Canadian Air Force wireless operator and air gunner

Keith Patrick, a wireless operator and air gunner with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), pictured (left) in 1941 and (right) in 1942 while stationed in Egypt, 108 Squadron. (Photo by Georgia Kirkos/McMaster University).

Keith Patrick was returning from a successful bombing mission in Arras, France when his Halifax bomber was chased and shot down by enemy fighters.

It was June 12, 1944, six days after D-Day.

The plane crashed in a field near the village of Gournay, killing four of the seven crew.

Patrick, a wireless operator and air gunner with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), was badly injured but alive. For the next three months, Patrick, pilot Don Fulton and bomb aimer Lyle Wilson relied on the brave members of the French Resistance and local families in the village of Renty to hide and care for them in the German-occupied area. The airmen stayed there until the area was liberated in September 1944.

Patrick’s RCAF escape kit, cloth maps, flight logbook, photographs, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings and many other materials are now part of the new Keith Patrick Archive at the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University Library.

“Keith Patrick’s archive arrived with every item well documented and described, so that you really get a good sense of his war experience,” said Christopher Long, archives arrangement and description librarian.

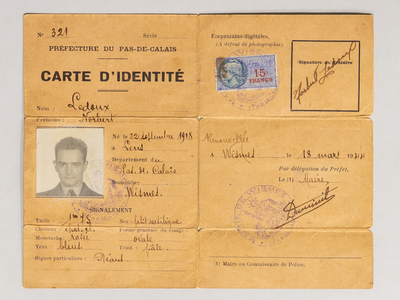

“We have 300 photographs that tell us about his training, wartime and the places he went. There are photos of planes, including images taken from the air. There are newspaper clippings from when he went missing in action, as well as a false French identification card that was created for him.

“This is an incredible story of survival, heroism and the accidents of history.”

Born in 1918, Patrick served in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) from 1940 to 1945. Hailing from Saint John, N.B., he came from a family of nine boys, five of whom would go on to serve in — and return from — the Second World War. He and his brother, Edmond, are the only known brother escaper-evaders of any Allied air force during the war.

Patrick completed a full tour of duty in North Africa with the Royal Air Force (RAF) 108 Squadron. It was during his second tour with RCAF 427 Squadron when he was shot down. He would go on to retire from the air force in February 1945 as a flight lieutenant.

McMaster library boasts a large number of wartime maps, including Second World War escape and evasion maps. The collection features maps printed on materials like tissue paper or artificial fabrics like rayon that aided downed air crews and prisoners of war in escape and evasion.

Patrick’s maps include two made of silk — including the one he had on him when his plane went down — and are the first of their kind to be added to McMaster’s collection.

The usage of silk maps has an interesting history, says Saman Goudarzi, cartographic resources librarian.

“Silk maps can be traced all the way back to the third century BC in China,” she said.

“This material was often used because it was more durable than paper, did not dissolve in water and could be easily folded into small sizes. Soldiers also stuffed and hid silk maps in their boots or lined them in their jackets for an extra layer of warmth.”

Patrick and his family made the decision together to donate his archive. His daughter, Janet MacNeil, helped facilitate the gift. McMaster was a natural recipient as MacNeil, her husband Peter, and her sister Charmian Patrick are alumni.

MacNeil and her father co-wrote a book in the early 2000s about his experience, To the Stars: Memories of a Wireless Operator-Air Gunner During World War Two. She said her dad was humble and rarely spoke about the war until she was much older.

“He did love to teach us how to march when we were kids, which was a lovely memory,” she said with a laugh. “He would put bagpipe music on and have us march around the house for fun.”

MacNeil said he watched Remembrance Day services on television but did not attend in person. Instead, MacNeil would take her dad in his later years out to dinner each Remembrance Day, convincing him to wear his jacket with his air force crest and rows of medals.

“People would come up to him and thank him when we went for that annual dinner,” said MacNeil. “He said the people who didn’t live through the war or were injured were the heroes, and that the families who saved him in France were the heroes. The people in the restaurant helped show him that they cared about his sacrifice.”

The Keith Patrick Archive will be ready early in the new year for research use. Long says he expects it will be of interest not only to researchers and historians, but also to undergraduate and high school students.

“To have a story that’s so clear and concise, and honestly thrilling, accompanied by such extensive documentation, can be a really effective first encounter with archival research,” said Long. “I think there is great potential for the archive to be activated as an educational resource for students who may be encountering archives for the first time.”

Patrick passed away peacefully at the age of 102 on April 29, 2021 in Kitchener, Ontario. He is remembered fondly by his family and friends. He had also stayed in contact with the Fillerins, the French family who saved him, and as it turned out, many other airmen.

MacNeil says her dad was happy when they discussed his war materials being available to the public at McMaster.

“To know that his story is going to go on, I think that was a gift for him,” she said.

Helpful links

William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections website