Hours to discover: Researcher studies how time really did get away from people

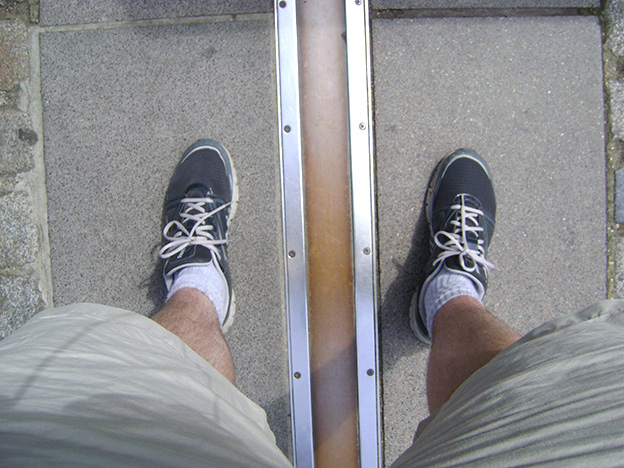

Researcher Scott Johnston stands at the prime meridian in Greenwich, England. Johnston's work focuses on the politics of time, specifically at the 19th century International Meridian Conference.

We take it for granted that when it’s noon in Toronto, it’s also noon in Hamilton.

But that wasn’t always the case.

In fact, before world leaders finally got together in 1884 to hammer out a standardized system of time-keeping, local times varied wildly.

A table published in 1857 shows that when it was 11:51 a.m. in Toronto, it was 11:53 a.m. in Buffalo, 11:36 a.m. in Detroit, 12:14 p.m. in Montreal and 12:23 p.m. in Quebec City.

This wasn’t a big deal, says History PhD candidate Scott Johnston, because travel at the time wasn’t very fast: you couldn’t get from one town to another quickly enough for a difference in time to matter.

That all changed, however, with the arrival of the railroad. Railway companies began independently adopting their own local times, which led to accidents and near misses on the tracks.

Though England’s Great Western Railway began using a synchronized “railway time” in 1840, the idea of using a common time didn’t catch on in North America until 1853, when a train accident killed 14 people in New England.

Even then, it didn’t enter widespread use in the US until 1883 – just a year before the International Meridian Conference, held in Washington, DC.

That gathering, which brought together delegates from 26 nations mainly in an effort to determine a common prime meridian, is the focus of Johnston’s research.

“Clocks and time are such a big part of our lives, but we never stop to think about why we use them in the way we do,” he says. “It’s important to understand that the way we do things isn’t the way things have always been done.”

Johnston says that once delegates agreed on Greenwich as the world’s prime meridian, cities around the world began to synchronize their clocks, usually with telegraph signals.

As with any kind of technology, however, the telegraph system didn’t always work, creating opportunities for some enterprising individuals.

“There’s a great story about a woman in London who would go to Greenwich to get the correct time and then go door-to-door, selling it to those who wanted the official time,” says Johnston. “This sort of thing went on until the 1940s.”

Johnston says that understanding how one system of standard time won out over all others helps us to understand the imperial relationships of the 19th century.

“Time is a constant in our lives, but it has a history of its own,” he says. “It’s very much a product of the time in which it was organized.”