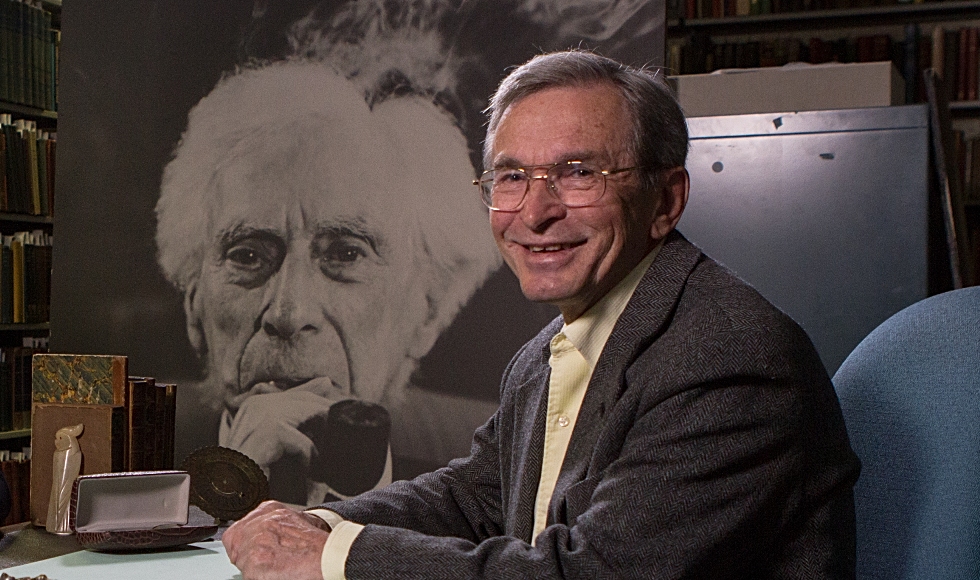

Honorary Archivist Ken Blackwell: How I met Bertrand Russell and other stories

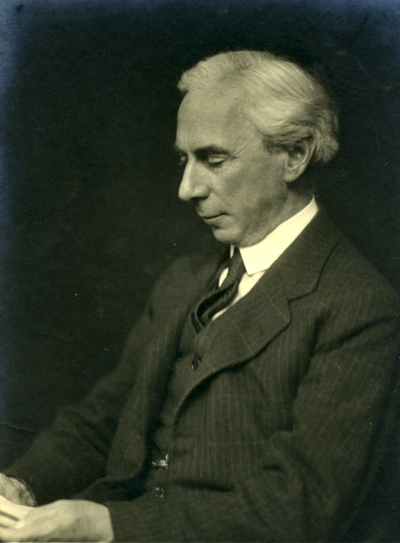

Ken Blackwell (pictured) has spent the last five decades studying the archives of pacifist, philosopher and Nobel laureate, Bertrand Russell. Now, he offers personal insights on what it was like to meet Russell and to work with the papers of one of greatest intellectuals of the 20th century.

In 1968, Ken Blackwell arrived at McMaster. Before then, he had been working in London, England, employed by the literary agent of renowned pacifist, philosopher and Nobel laureate, Bertrand Russell, meticulously cataloguing Russell’s vast archives.

When the news broke that McMaster had purchased Russell’s much sought-after papers, Blackwell was soon approached by the University’s chief librarian William Ready who offered him the position of Archivist (later Russell Archivist) at McMaster. It’s a position he held for 29 years until “retiring” in 1996. Since then he has been a very active Honorary Russell Archivist.

Blackwell recently talked about his experiences working with McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Archives in an interview published in the latest issue of Hamilton Arts & Letters Magazine.* He was interviewed by McMaster media relations manager Wade Hemsworth, the author of three non-fiction books, who spent 25 years as a reporter and editor at The Hamilton Spectator.

The following are selections from that interview, Kenneth Blackwell: The original Russell Archivist, and have been republished with the permission of Hamilton Arts & Letters Magazine:

Wade: You’ve been known to spend your vacation pursuing material for the archives. You spent your working life, and now 21 years of your retirement entirely concerned with the work of one other person. Why?

Ken: Well, at the ground level, the works suits me, my abilities, my

interests. But Russell made a mark on me back when I was 20 years old. It was the time of the Cuban missile crisis, and a few months after the crisis had passed, a book by him appeared. It was for sale in my local drug store and I bought it and I still have it. I was absolutely fascinated how this 90-year-old man could write a book, and such a good book. From him—from this interest—I switched my majors in college from Commerce to Economics, and that led within a couple of months to Philosophy, because I wanted to know what Russell knew.

Well, that was a big order because I soon found out that he had written a tremendous range of books from atomic theory to marriage and morals, happiness, history, philosophy, books on British history. He had written travel books for goodness sakes! He’d gone to the Soviet Union in 1920, interviewed Lenin. It was endless. I guess it is endless, because we’re still finding new materials.

Wade: You had two very different personal introductions to Bertrand Russell, and they were both on the same day, as I recall.

Ken: I was returning from Ireland to London and I went through Russell’s town in North Wales, Penrhyndeudraeth, and I stayed there a couple of days. It took that long to get up the courage to phone his home and ask to meet him. I talked to his secretary and he said, well come at noon today and you can meet Lord Russell. And so I went there and I shook Russell’s hand and talked to him very briefly for a moment. Then I left and I had the feeling that others have had, that, as a stranger, you shouldn’t intervene in some famous old person’s life and disturb him.

But as I was walking away from his home down the lane, the secretary came running after me and he said, ‘Are you the Kenneth Blackwell we wrote to in Victoria, British Columbia?’ And I was. Russell decided to sell his archives and so he had written around to people who might know where other papers of his were. My name had been given to him by Russell’s bibliographer. And so that letter had arrived at home in Victoria, but I did not know of it.

I was invited back to tea that day, and that lasted about two and a half hours. It went by in a couple of seconds, it seemed to me. I was able to show Russell my own bibliographical work.

We talked about many things. We talked about President de Gaulle’s visit to Russia that summer. This was July 1966. I asked Russell, what do you think is the purpose of that visit? Russell said, ‘Well, I don’t know, what do you think?’ And I had to pick myself up from that one because, well, I didn’t think, I just asked.

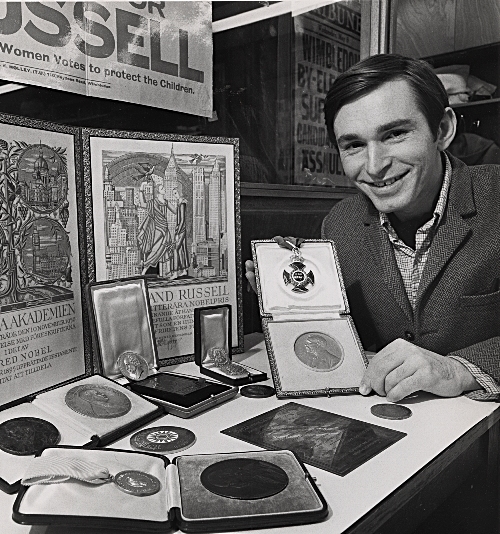

Anyway, very soon after that, while I was still in Penrhyndeudraeth, I was offered a job sorting his papers in his basement. And so I had my first Russell job. It lasted three weeks, until the papers were carted off to London. My second Russell job was working on the catalog of the Russell papers in London. That’s this 340-page book that was published just at the time that William Ready, the new McMaster University Librarian, got interested in the Russell papers. The purpose of this catalog was to sell the papers, but at the same time, it’s got a lot of scholarly importance to it, and Russell even wrote a preface for it.

Wade: Ken, how would you say that your view of Bertrand Russell has changed during the time that you’ve been working with his archive?

Ken: Well, my initial view changed quite quickly. I was used to that very dry, very rational persona with which he wrote his books. Remember he was a Cambridge graduate from 1893. He spoke in a peculiar way. His accent was his own. Every syllable was individually enunciated. You never had any doubt of what he said. In meeting him and having tea with him from time to time, I realized that he was a much warmer, much more emotional person than I thought. But at the same time, I’m just reading the papers in the basement and it was extraordinary what psychical—what emotional difficulties he had had in his life. Remember, I hadn’t gone through much. I was 23.

Russell had written about various crises in his life and had put them in his autobiography, but it hadn’t been published yet, and so I was able to read his autobiography before it was published. That changed my view of him a lot. Well, first of all there’s the discovery of one affair after another, until this last marriage when he settled down with Edith. He didn’t believe that marital ties should be bonds, in the sense that they shouldn’t be chains. People should be free to express their love in whatever way was natural. Well, for him, it was natural to express his love to many different women, sometimes concurrently. The big outcome of that, for us, is that he would write letters to these women. In one case, 1900 letters, in another 802, and we have them now.

Wade: This is a broad question, but why do you think it’s still important to study Bertrand Russell?

Kenneth: Well, he’s a master of the English language first of all. Even if you disagree with his opinions, you can still study how well he expressed them. He went through these personal difficulties and wrote about them. You can see things that have come up in your own life coming up in Russell’s life and how he dealt with them. His philosophical work is now part of the history of philosophy, but as recently as two years ago, the last volume of our Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell on philosophy was published and people have only begun to study that volume. In politics, he’s very valuable because he sees through the posturing and the lies and gets to the heart of the matter.

One thing that has impressed me hugely, as I’ve come to know Russell’s life, is what I would call the self-sacrifice of his last 10 or 15 years. Here is a man who thought that he would retire and live a life of quote ‘elegant leisure’, reading all the great books that he should have read when he was younger. Instead, current events tied him to his desk to write articles about nuclear disarmament, about the Vietnam War, and other political matters. At times, he will say in reply to somebody requesting another article on nuclear disarmament, ‘I can’t think of anything new to say on this topic. Don’t ask me for a while.’

Wade: It’s been nearly 50 years since Bertrand Russell died. During his life as a public intellectual, he was immersed in intellectual pursuits and was also a figure in popular culture. It was a time then, when popular culture still embraced great thinkers. Do you feel that thinking has gone out of fashion since then?

Ken: I think ‘thinking’ has merged with other things. There are obviously people who are being interviewed in the media who are deep thinkers, but they’re also media academics, and you know they’re getting a lot of money for what they have to say. Someone who just thinks and writes without regard to public opinion, that’s pretty rare now, especially at the highest level. There’s always this element of celebrity with it now.

Now, one of the great celebrities of our time is Paul McCartney. He went to see Russell in 1965. He talked about it on some television programs, and his biographers mention it. McCartney says that he spoke about Russell to John Lennon and John Lennon was encouraged to come out against the Vietnam War because of what he had learned about Russell. You may have seen that in the Russell archives, there’s a lovely card from John Lennon with a drawing of him and Yoko.

Russell had a special place in English celebrity-dom. He became known to the wide public through talking on the BBC, and at that time—this is, say, 1945—there was only the BBC in Britain, there were no private stations, and Russell gained a tremendous reputation with the public of being a high-level thinker. His History of Western Philosophy was published then and they couldn’t print enough copies to satisfy the demand. Paper was short in those days right after the war, and his writings became an object of desire.

He went on to get the Order of Merit and the Nobel Prize all within a very few years, and so he had a tremendous reputation among the public. Then along came nuclear weaponry held by both the American side and the Russian side, and Russell could see nothing but disaster for mankind if there were another World War. That’s what he used his celebrity to campaign against. Anything he said would be recorded, and that went on until nearly the end of his life.

Wade: What constitutes a good day as Bertrand Russell’s archivist?

Ken: The discovery of new documents. Secondly, further identifying ones that we already have, as maybe the signature’s been hard to read for these 50 years and now it’s become clear who wrote it. I don’t deal much with researchers anymore, but still they come and ask me things and helping them is satisfying. I retired with some large unfinished projects, like the Russell Archives research catalogue BRACERS. If I can make headway in either one of them on a day, that makes it a good day too. That’s without the discovery of new things. And they’re pretty frequent.

Read the full interview with Ken Blackwell

*The latest issue of Hamilton Arts & Letter Magazine was edited by McMaster University Library archivist, Rick Stapleton to commemorate the 50th anniversary of McMaster’s acquisition of the Bertrand Russell Archives.