Green space, benches, sidewalks needed to create age-friendly cities

For seniors, the benefits of walking are huge.

Research shows that regular walking improves balance and coordination, builds muscle strength, maintains heart health and staves off depression– all important factors healthy aging.

The question is how to make walking part of seniors’ everyday lives.

Now, a new study led by Antonio Paez, a professor in McMaster’s School of Geography and Earth Sciences, suggests that where a senior lives plays a significant role when it comes to mobility.

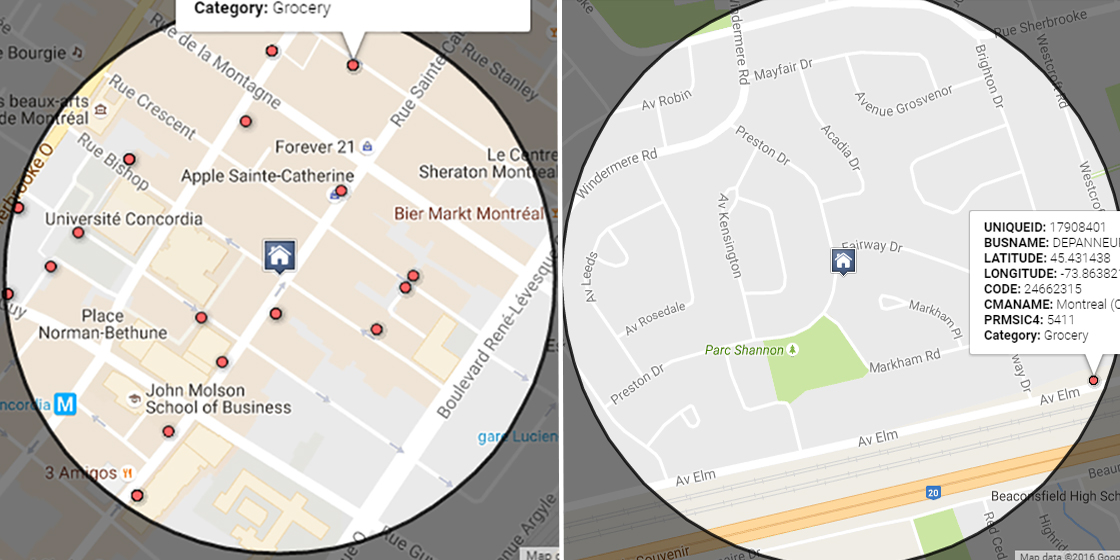

The study, part of the Walk the Talk project and funded through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Aging shows that seniors walk more when they live in downtown, pedestrian-friendly areas, closely located to what Paez calls ‘destinations that matter,’ the places seniors go to on a regular basis.

“We wanted to look at factors that encourage seniors to stay healthy and active,” says Paez whose study looked at the mobility patterns of seniors in both urban and suburban neighbourhoods. “We were interested in finding out what it is about the physical characteristics of communities that encourages, or discourages seniors to walk.”

Working in collaboration with researchers from The University of British Columbia and Polytechnique Montréal, Paez and his team observed the walking patterns of older adults in Montreal and Vancouver. They measured the frequency, length and duration of trips and also looked at the physical characteristics of neighbourhoods to find out whether they were conducive to walking.

They found that seniors walked the most in neighbourhoods where they lived within shorter distances of ‘destinations that matter’ such as coffee shops, restaurants, churches, banks, grocery stores, pharmacies and other services.

The study also revealed that pedestrian-friendly areas with traffic calming features– like speed reduction zones– properly maintained sidewalks, and public spaces that provide shade and benches, were also important factors in increased mobility.

“We found that in Montreal, walking trips taken by seniors in downtown areas tend to be more frequent and shorter, but even a short trip provided a rich landscape of opportunities for seniors,” says Paez.“Whereas in suburban Montreal, walking trips are less frequent, longer and don’t provide even a fraction of the opportunities– it’s inconvenient to walk and there simply aren’t many places to walk to.”

Paez says that having easy access to ‘destinations that matter,’ not only encourages seniors to walk more, it can also contribute to emotional well-being.

“Coffee shops, for example, are hubs for social activities,” says Paez. Groups of seniors get there in the morning and they chat. That’s part of their social life. Inability to maintain social connections is tied to depression for older people, so having these kinds of opportunities nearby that help maintain social contact is essential.”

Paez says there’s a lot cities can do to reduce barriers to walking and help create more aging-friendly communities.

For example, creating more green spaces, installing benches, making sure that pedestrian lights leave seniors with enough time to cross the street, providing good sidewalk connectivity and ensuring that there are curb cuts– small ramps cut into the sidewalk at intersections– so seniors, who may be unsteady, don’t have to step on, or off the curb.

“We need to make it convenient for seniors to walk,” says Paez. “In many cases, we already have the basic infrastructure in place. The challenge is retrofitting spaces in such a way that it makes them amenable to walking.”

Paez admits that moving to a downtown area may not appeal to everyone, especially to those living in the suburbs who may be reluctant, or unable to leave their communities for a more urban environment. But he encourages municipalities to develop future projects with seniors in mind and adds that in some instances this is already starting to happen.

“There are many newer developments that simulate a little village,” says Paez. “They are recreating a downtown location, which is more amenable to live in and is surrounded by lots of services. This should be a draw for seniors and it will definitely be more convenient.”

But Paez says whether you’re 35, or 65, the key to mobility is to start looking for ways to incorporate walking into daily activities regardless of where you live.

“We know that eventually everyone ceases to drive. My suggestion is to think about walking as something you do as part of everyday life, not just as an exercise,” says Paez. “We talk about aging as a process that starts at age 65, but it’s a process that begins the moment we’re born. Walking as a habit is established early in life, so if you can get into the habit of walking as early as possible, that’s important.”