Exploring the “Quantum Revolution”

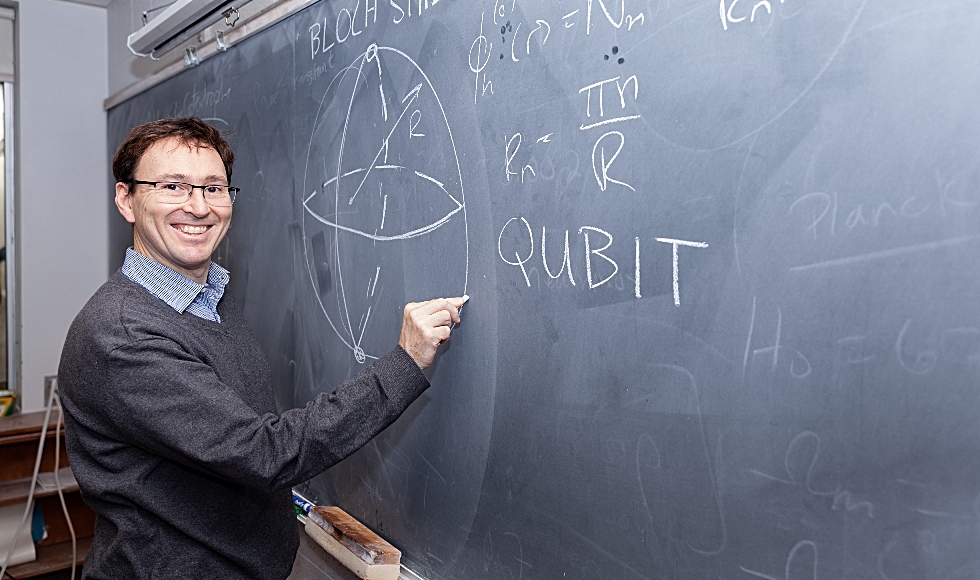

An undergraduate course taught by Duncan O’Dell, a professor of quantum physics in McMaster’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, is providing students from a number of disciplines with an introduction to the theory behind quantum computing and other rapidly evolving quantum technologies

When most of us think about quantum physics, things like teleportation, warp drive and time travel – ideas popularized by Star Trek and other sci-fi classics – are what come to mind.

While it’s unlikely that any of us will be “beaming up” or traveling at warp speed anytime soon, many technologies based on the principles of quantum mechanics are rapidly moving beyond the realm of science fiction, into science fact.

In October, Google claimed to have achieved “quantum supremacy,” also known as “quantum advantage,” after unveiling a computer that, by harnessing the laws quantum mechanics, was able to perform a calculation in less than four minutes that even the world’s fastest supercomputer would need 10,000 years to complete.

In the not-too-distant future, quantum computing and other technologies based on quantum mechanics could lead to an explosion of innovations, from the development of sensors capable of detecting oil and mineral deposits buried deep beneath the earth, to the creation of unbreakable codes and, yes, even teleportation, albeit on a limited scale.

Now, an undergraduate course, offered by McMaster’s Department of Physics and Astronomy is providing students from a number of disciplines with the opportunity to explore the theory behind what many are calling, the “quantum revolution.”

The third-year course (Physics 3QI3: Introduction to Quantum Information), which will run throughout the winter term, focuses on introducing students to what’s known as “quantum information,” an area that combines computing theory with the principles of quantum mechanics.

“I designed the course to meet the needs of students who are interested in this whole new subject,” says course instructor, Duncan O’Dell, a professor of quantum physics in McMaster’s Department of Physics and Astronomy. “It was once a somewhat arcane area you didn’t need to worry about because it happens on such small scales, but now new technologies will increasingly be based on quantum mechanics, so it’s going to become a part of our everyday lives.”

O’Dell says the course, which doesn’t require students to have taken any previous courses on quantum mechanics, will cover a range of topics, including quantum supremacy and the history of quantum computing, quantum cryptography, teleportation, quantum circuits, quantum entanglement and a host of other topics. But O’Dell’s first task will be to provide a primer on the concepts of quantum mechanics, which he admits can be a bit mind-blowing.

“Quantum mechanics is really understanding how nature works on very small scales,” he says.

O’Dell explains that unlike classical computers which process information using binary “bits” made up of linear sequences of ones and zeros, quantum information exists on minutely small scales and is stored in what are called, qubits – atomic or subatomic particles such as ions, electrons or photons which, due to the counter-intuitive laws of quantum mechanics, are capable of being in a state of one and zero simultaneously, a phenomenon known as quantum superposition.

“This allows quantum computers to do massively parallel computing because every qubit in the computer can be in a superposition of both zero and one at the same time,” says O’Dell. “This means that these computers can do many calculations with all the possible values of all the bits, so there are certain things they can do much faster than classical algorithms.”

“These concepts are deep – some of the deepest things students will hear at university,” he continues. “It shows us that the world is more than you can see, and it’s stranger than you could have imagined, so it’s important to expose students to these ideas.”

O’Dell says that while quantum mechanics has long been part of undergraduate physics education, this course is the first of its kind at McMaster to bring together students from multiple disciplines including physics and astronomy, engineering physics, and mathematics, as well as students from the Integrated Science (iSci) and Life Sciences programs.

“Increasingly, quantum mechanics is moving from scientific theory toward technological innovation and commercialization, so lots of different skill sets are required,” says O’Dell. “Many students will go into careers where they’ll need to know this stuff, and this course is a great opportunity for students to be in this wave of people that can contribute to this technology.”

Elsie Loukianchenko, who graduated from the iSci program this spring, took the course when it was first offered last winter.

“I was interested in the course because quantum computing has been a fascinating field for me for a while – it’s a beautiful crossover of math and physics with real-life tangible applications, making it an incredible field to be a part of,” she says. “Having a course in this super-new topic is very rare, and I felt I had to take it.”

Loukianchenko, who is now pursuing her a master’s degree in applied physics in the Physics for Quantum Devices and Quantum Communications stream at the University of Delft in the Netherlands, says she encourages other students to take the course.

“it’s a great general interest course and a wonderful asset to have, especially if quantum physics is a field you’re interested in pursuing,” she says.

O’Dell is hoping that, whether students plan to pursue careers related to quantum physics or not, they’ll come away from the course with a deeper appreciation and interest in this complex and rapidly evolving area.

“Quantum mechanics is absolutely everywhere,” he says. “It’s the forefront mystery in physics. Although the mathematics is there, the concepts are not yet well-understood, so there’s a lot of really interesting work still to be done.”