Celebrating 30 years of midwifery education at McMaster and in Ontario

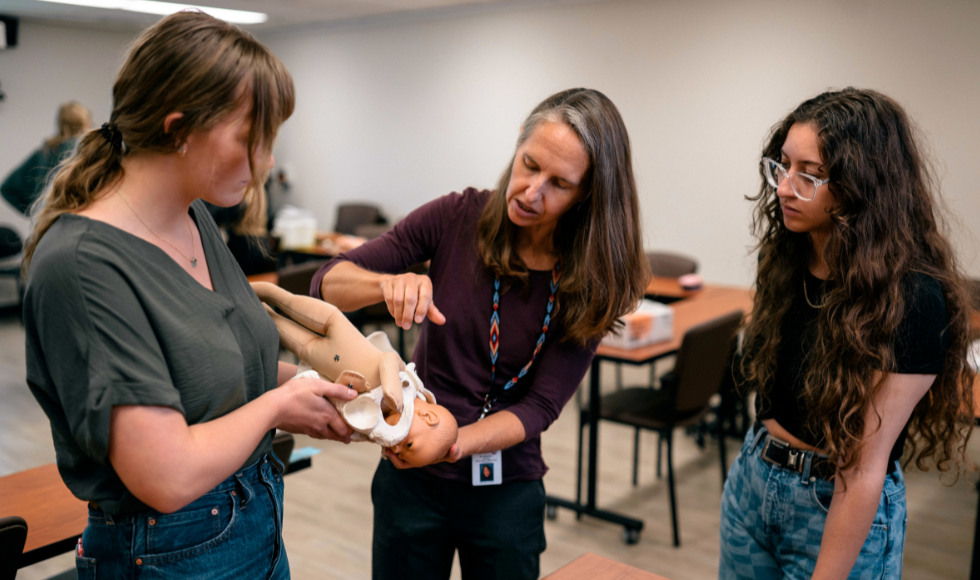

Liz Darling (centre) is the director and assistant dean of the Midwifery Education Program at McMaster.

McMaster University is celebrating 30 years of midwifery education, and it’s all thanks to the pioneering force of the hard-working midwives who were there when the program launched.

In 1994, regulations came into effect that allowed for the funding and integration of midwives – health care specialists who focus on pregnancy, birthing and postpartum care for birthing parents – in Ontario’s health-care system. At the time, there were only about 70 midwives in the province.

So in 1993, a year before those regulations would come into effect, a consortium was formed between McMaster, Laurentian University and Ryerson University (now named Toronto Metropolitan University) to create an undergraduate program for midwifery.

The program at McMaster was originally led by four pioneering educators. Karyn Kaufman, the first director of the program, Eileen Hutton, Patricia McNiven and Helen MacDonald. McNiven is still with the faculty today, while MacDonald retired earlier in 2023.

“I’m grateful for the support that those who came before me have given me and have given to help the profession to grow and get to where it is here at 30 years,” says Liz Darling, the current director and assistant dean of the Midwifery Education Program at McMaster. “I just want to express my gratitude for all the people who worked so hard and on whose shoulders we stand. Because of them, we can continue to build and move forward.”

In that first year, seven students were enrolled. The next year, the program grew to 11, which included Darling among them. Since then, it has quadrupled in size and now welcomes 45 students annually.

“The program was set up to draw on the tradition of how midwives in the province had been learning, which was through apprenticeship models. And so, the degree incorporates a large amount of time where students are able to learn by working in a midwifery practice,” Darling says.

By the time students graduate, most students will have been involved in about 100 births. And of those, students are required to act at as the primary midwife at 40 births.

It was also important in the development of the program that it be offered as direct entry, meaning no prior post-secondary qualifications are required. The direct entry approach mirrors how midwifery is taught in some other countries, like the Netherlands, which was one of the places Canada looked to when deciding how midwifery would work in Ontario.

“A few people come to us after having studied nursing and there are people who enter the program after having worked as doulas, but the majority of students who come into the program now haven’t attended births before and don’t have previous clinical experience.”

Increased demand for midwives

Over the last 30 years, demand for midwives has skyrocketed. That demand saw an incredible rise during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic as birthing parents sought to give birth in the safety of their homes.

But keeping up with demand has been a challenge. “There are lots of places that are looking to hire midwives and not enough midwives available.”

Another challenge is the availability of education. Limits to scaling up stem from the need to have midwives available to teach so that students can gain necessary clinical experience.

In 2022, McMaster started offering the first master’s degree for midwifery in Canada.

“Part of our vision for that program has really been to support midwives to expand their knowledge and skills, particularly in areas of leadership, and to help them drive change in the health-care system,” Darling says.

Looking to the future

The core work done by midwives is focused on pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period. But Darling sees a broader future for midwives in Ontario – one where midwives can use their knowledge and skills to address unmet needs the health-care system, especially in smaller communities.

“Having midwives be able to fill other gaps can really help to leverage the benefits that midwives might be able to offer.”

Darling sees opportunities for midwives to provide Pap smears, and contraception and abortion care. And in places with limited access to other primary health-care providers, midwives could help fill the gap and provide service to young children who are beyond the six-week postpartum period.

“Midwives are lucky because our model allows us to spend time with people. We truly get to know them. That is part of what helps build people’s comfort and satisfaction in the care that they receive.”