World’s tiniest gingerbread house created at McMaster

Some people go big with their holiday decorations. Travis Casagrande goes in the opposite direction.

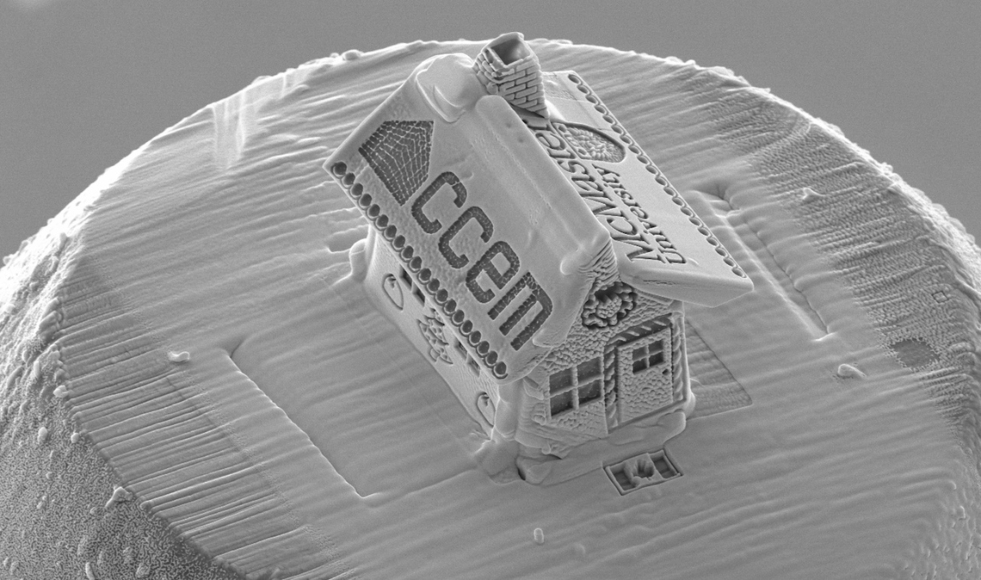

In a feat of skill and technology, the research associate at the Canadian Centre for Electron Microscopy at McMaster University has created and stacked two richly detailed decorations, yet both of them together are barely taller than the diameter of a human hair.

Casagrande cut and etched a gingerbread house from silicon, complete with sharply defined bricks and trim and a Canada flag for a welcome mat. It may be the smallest house ever created – about half the size of one made in France last year.

The tiny new wonder, as a set of dramatic photos reveals, is in turn resting like a small cap on the head of a winking snowman that Casagrande made from a material used in lithium-ion battery research.

The final photo reveals that the snowman is standing beside a human hair that looks like a redwood trunk by comparison.

Under intense magnification, Casagrande dug out the pieces of the decorations with a beam of charged gallium ions, which acted like a sandblaster.

Casagrande drew national attention in 2017 for a similar display of skill and technology when he used the same equipment to carve a tiny Canadian flag flying from a pole, all set inside an almost imperceptible hole in the back of a penny.

While the spirit of the new decorations is festive, the intention of the project, Casagrande explains, is to demonstrate the capabilities of the centre, which is a national facility with a suite of 10 electron microscopes and other equipment used mostly for materials research by Canadian and international users from both the academic and industrial sectors.

Unlike a traditional desktop microscope that focuses light through optical lenses, an electron microscope uses an electron beam and electromagnetic lenses. The wavelength of these electrons is roughly 100,000 times smaller than that of visible light, allowing far greater magnification.

Casagrande hopes the holiday project will stir scientific curiosity among the public and let other researchers see what the centre is capable of doing.

“I think projects like this create science curiosity,” Casagrande says. “I think for both children and adults, it’s important to be curious about science. Looking into how this was made leads to more interest in science, and that builds more science literacy, which allows everyone to make better decisions.”

The focused ion beam microscope that Casagrande used to make the festive decorations is the same one he and others use to prepare much, much smaller samples for use in the centre’s powerful transmission electron microscopes, which are capable of capturing images down to the level of a single atom.