Scientists map genome of giant, shelled mammal known as the ‘glyptodont’

Scientists have sequenced the entire mitochondrial genome of the ancient glyptodont, a giant, strange mammal and ancestor of the modern-day armadillo, which first appeared approximately 4 million years ago, roaming the Earth until its extinction during the Ice Age.

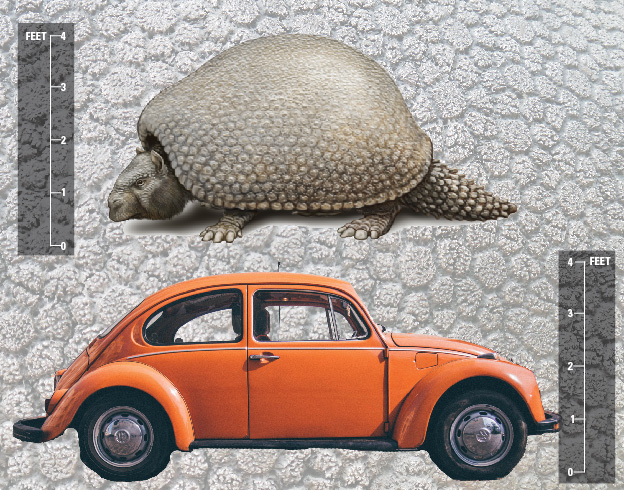

Roughly the size and weight of a Volkswagen Beetle, the glyptodont was distinguished by its massive, heavy shell of armor, and a club-shaped, armored tail.

Its mysterious evolution and remarkable skeletal adaptations have long fascinated and perplexed biologists and geneticists. Though it had been apparent the mammals must be related, it was not clear until now that their ancestral connections were much more recent than previously thought.

“The data sheds light on the familial relations of an enigmatic creature that has fascinated many but was always shrouded in mystery,” says evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre and the senior Canadian researcher on the paper. “Was the glyptodont a gigantic armadillo or weird off-shoot with a fused bony exoskeleton?”

Glyptodonts’ place within the larger group of mammals known as Xenarthra, which includes anteaters, tree sloths, extinct ground sloths, extinct pampatheres and armadillos, has remained unresolved.

Though elements of the mystery remain – including the cause of its extinction – the latest findings suggest the glyptodont is deeply nested within the armadillo family and best treated as a close relative, say researchers.

The scientific team from McMaster University, the Université de Montpellier (France), Massey University (New Zealand) and the American Museum of Natural History, gathered fossilized specimens and successfully extracted genetic material from a fossil found in Argentina of the Doedicurus, one of the largest and last known glyptodonts.

Using novel techniques to extract, isolate and sequence a complete genome of the extinct animal, the team compared it to its living counterparts to confirm its lineage.

“Ancient DNA has the potential to solve a number of questions such as phylogenetic position—or the evolutionary relationship—of extinct mammals, but it is often extremely difficult to obtain usable DNA from fossil specimens,” explains Poinar. “In this particular case, we used a technical trick to fish out DNA fragments and reconstruct the mitochondrial genome.”

Evolving in the warmer climates of South America before migrating north, the glyptodont became extinct during the last ice age though its descendant, the armadillo, would survive.

The study is published online in the Cell Press journal Current Biology.