Reflections on Bertrand Russell’s relevance on 150th anniversary of his birth

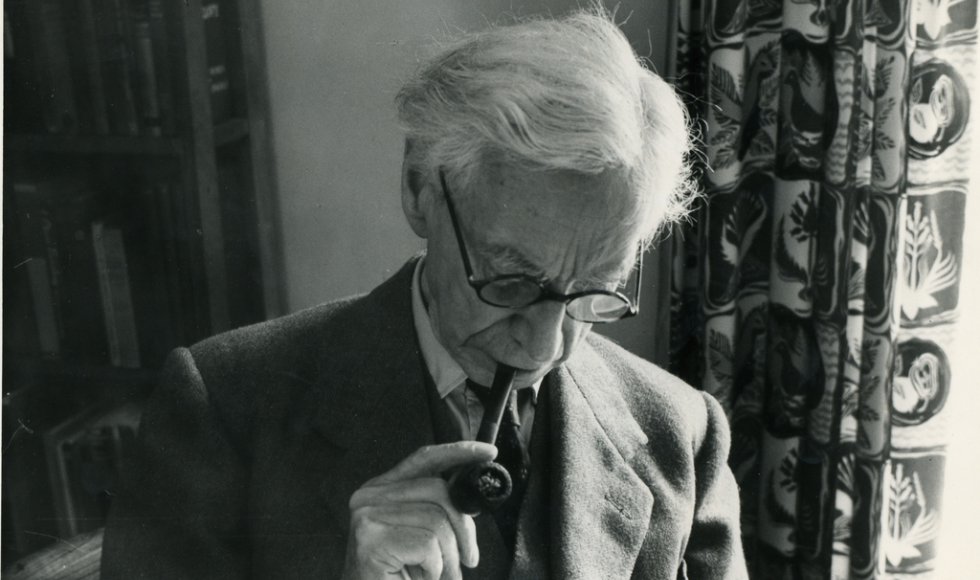

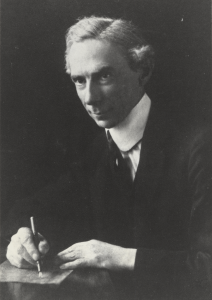

Bertrand Russell was a British philosopher, logician, essayist and peace advocate. His archive and personal library have been at McMaster since 1968.

“Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.”

– Bertrand Russell, 1967

Birthdays are often a time for reflection, especially as the years pass, so it is apropos to ruminate on the illustrious Bertrand Russell on the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Russell, who lived from 1872-1970, was a British philosopher, logician, essayist and peace advocate.

Considered a great thinker of the 20th century, he is widely credited with transforming logic and philosophy, as well as addressing numerous social and political issues of contemporary and continuing significance.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950 was awarded to Russell “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.”

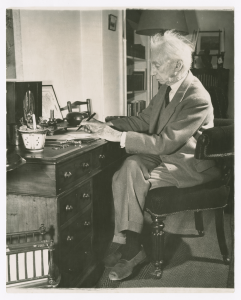

The archive and personal library of Russell have been at McMaster library since 1968 and remain the most heavily used research collection. Scholars from around the world visit McMaster to pore over Russell’s manuscripts and correspondence with individuals as diverse as Nikita Khrushchev, John Lennon, Alfred North Whitehead and Ludwig Wittgenstein. The archive also contains the aforementioned Nobel Prize.

The Bertrand Russell Research Centre (BRRC) was subsequently established in 2000 to publish Russell texts and foster Russell research.

We asked McMaster’s Andrew Bone, senior research associate, BRRC; Nicholas Griffin, scholar in residence, BRRC, and Alexander Klein, director, BRRC, to weigh in on Russell’s impact today, boil down his influence into a single word (not an easy feat), and to share fascinating, lesser-known stories as we mark this momentous occasion.

As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the birth of Bertrand Russell, what makes his work relevant today?

Bone: In an eloquent prologue to his Autobiography Russell wrote that his life had been governed by three passions: “the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.” I think that this striving for love, truth and justice speaks to our time just as powerfully as it did to Russell’s.

Griffin: During the first half of the twentieth century Russell put forward a great raft of philosophical ideas which, in one way or another, dominated philosophical discussion in the English-speaking world for the rest of the century. With the opening of his archives, we’ve found he left almost as many equally important ideas unpublished and that many of the ones he did publish had been very badly misunderstood. We are still at the beginning of sorting all this out: it’s a very exciting time to be working on Russell’s philosophy. His standing as a philosopher now is even higher than it was when he died.

Klein: To figure out how to move forward today, we must take an interest in history. Russell is one of the most important architects of analytic philosophy, a style that continues to dominate the field, especially in the English-speaking world. He was also an extremely outspoken peace activist, and his vision of philosophy fits in with his wider social program. As western cultures are increasingly at odds over the role we should give rationality (versus ethnic or national or partisan allegiance) in public life, Russell has a lot to say to us.

How would you describe Bertrand Russell in one word?

Bone: Prolific (Witness the size of the Russell Archives)

Griffin: This is the hardest question: I think I would have to coin one. I did once hear Ken Blackwell, who knew him, describe him as ‘decisive’ and I think that’s a very insightful one-word description, certainly as regards his writing.

Klein: Ingenious

What is one thing people might not know about Bertrand Russell?

Bone: There are many curious as well as inspiring and memorable episodes in Russell’s long life, including the credible reports of his death that surfaced in Western newspapers at one point during the year he spent in China (1920-21). Clearly it wasn’t only of Mark Twain’s demise that the rumours were greatly exaggerated! Russell lived another fifty years.

Griffin: I think it’s still not widely known that at the age of 91 Russell sent two personal emissaries for discussions with Zhou Enlai in Beijing, Jawaharlal Nehru in New Delhi and Sirimavo Bandaranaike in Colombo (Sri Lanka, then Ceylon) in an attempt to broker a negotiated settlement to the Sino-Indian border dispute. Serious discussions took place and Russell’s representatives carried diplomatic messages between the three capitals. Prospects for a settlement seemed very high, but in the end Russell’s efforts at shuttle diplomacy failed and the dispute remains unresolved to this day.

Klein: In 1907, Russell stood for parliament as the nominee of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Central to his platform was supporting the right for women to vote. This was such an unpopular position that at one speech opponents let a box of rats loose in the auditorium.

Any closing thoughts to share?

Bone: One hundred and fifty years after Russell’s birth, it is not easy to fathom his place in the popular consciousness today. But it remains the mission of the Russell Archives and Bertrand Russell Research Centre to shed as much light as possible on the incredibly rich and diverse life and times of a hugely significant thinker, writer, peace campaigner and social critic.

Klein: We have a very proud history of Russell scholarship here at McMaster. The Russell Archives are expertly maintained by the Library. And with the continued support of the Faculty of Humanities, the future for the Bertrand Russell Research Centre is bright.