Reflections on a presidency: A conversation with David Farrar

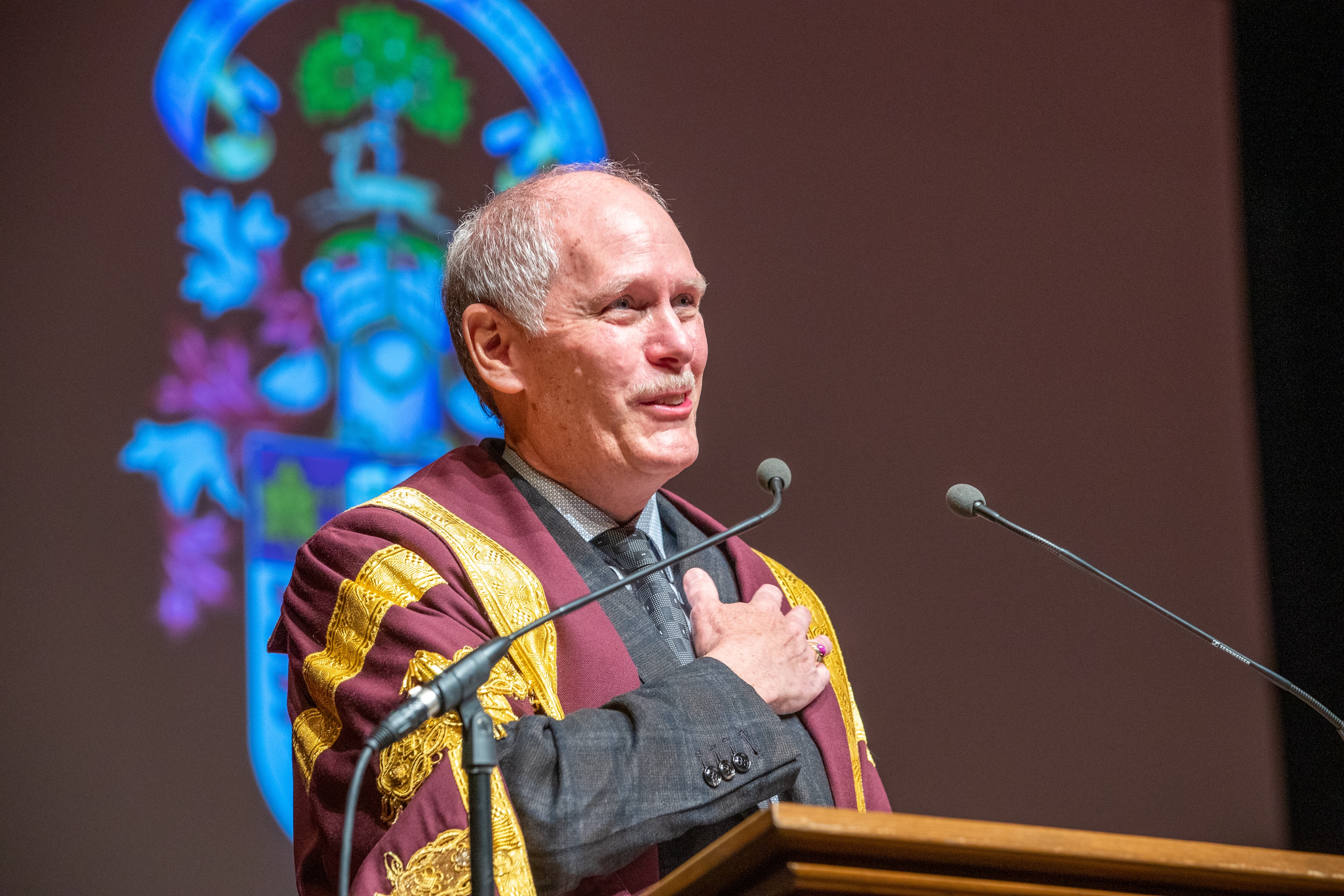

On June 30, David Farrar will conclude his term as McMaster’s eighth president. As he prepares for his next chapter, Farrar shares his insights on leadership in turbulent times, building on McMaster’s “radical roots,” and life after the presidency. (Photo by Georgia Kirkos, McMaster University)

When David Farrar arrived on campus in 2017 as provost, he never imagined that, just two years later, he would be leading the university through one of the most turbulent periods in its history as McMaster’s president.

“It’s not something I ever aspired to, but serving as McMaster’s president has been the honour of my career,” says Farrar, a chemist and accomplished administrator who, for the past 35 years, has held leadership roles at some of Canada’s top universities.

It may not have been a role he sought, but since becoming president, Farrar has navigated a pandemic and championed the development of McMaster’s first sustainability strategy and net-zero carbon roadmap. He has led the reimagination of the university’s innovation ecosystem, and supported initiatives to advance inclusive excellence and Truth and Reconciliation across campus with steadfast calm and a deep belief in McMaster’s capacity to make a transformational impact in the world.

On June 30, Farrar will conclude his term as the university’s eighth president. As he prepares to begin his next chapter, Farrar reflects on the past five and a half years, and shares his insights on leadership in turbulent times, building on McMaster’s “radical roots,” and life after the presidency.

When you became McMaster’s president, what did you hope to accomplish during your term?

When I came to Mac, I knew a bit about the university, but I hadn’t fully appreciated just what a unique place it is.

I knew about the problem-based learning approach that started here, the interdisciplinary programs, the evidence-based approach to medicine.

But once I got here, I learned about the many innovative aspects to McMaster’s teaching and research — our world-class vaccine discoveries, the Indigenous Studies Program that was the first program of its kind in the country, our global leadership in nuclear science, our amazing work on thermal energy conservation and district energy design, to name just a few.

I took on the president’s role because I wanted to deepen those approaches. I wanted to return McMaster to what I call its radical roots — to encourage that teaching and research innovation, to speed up the transfer of our research to real-life challenges, to encourage entrepreneurship and provide more opportunities for students to develop leadership skills.

I wanted to help the university move forward on the activities that were really having a major impact in the world. That may seem a bit idealistic, but at the same time, it just felt like there was such a great history at McMaster, and that was what I really wanted to build on.

What were some of the challenges you encountered as president?

I came to Mac to be provost, which is a job I think is a privilege to do because you sit at the nerve centre of the whole university, and you get to see everything the university is doing. But two years into it, I became acting president. In December 2019, the Board named me McMaster’s next president, and we ran into a number of very complicated issues very quickly.

The most significant one was COVID-19. By January, we knew it was circulating in China, by February we were seeing it start to move around the world, and by the first of March, it was here.

On the 13th of March, we closed our campus to in-person teaching and research, and we became a virtual university.

How do you prepare for something like that?

You take advice from a lot of great people who really contributed to moving us forward.

In fact, there was a lot of pandemic-related work already going on here at Mac. Many researchers were studying antimicrobial resistance and the possibility of new respiratory viruses, with an eye towards the next pandemic.

And several years before, the MacPherson Institute had invested in teaching and learning technologies, so we were ready to support everybody moving into the digital environment, but it was complex at that point in time.

First, it was “How are we going to get through the next three weeks of term?” Then “How are we going to run exams in the virtual environment?” And then “Maybe we should think about running virtual courses in the summer.”

We all thought we would be back in September, but of course, that never happened.

It was complicated, but the amazing part of it from my perspective was the collaboration. The entire leadership of the university met on Zoom every Monday morning. Not just the senior leadership, but the people responsible for our residences and food services and facilities and finances — all the areas of the university were there.

We just started working through what the issues were and how we were going to respond to them. The senior team was there — the president and the vice-presidents and the deans — to make the decisions, but all the other people who supported us were there too, and heard the decisions being made, so they understood them.

We also engaged our immunologists and infectious disease researchers in our decision-making, so we had the best information on everything from vaccines to personal protective equipment.

Our researchers were the first in Canada to isolate the genetic sequence of the virus, they were key advisors to governments and public health agencies and developed ways to track the spread of the virus through wastewater.

McMaster came through the pandemic exceptionally well and, looking back, I think the approaches we took were absolutely the right approaches.

Are there any other challenges you faced?

Another real challenge for us has been the decline in funding support from both levels of government. Ontario is tenth out of 10 provinces in terms of per-student funding.

We’ve managed to balance our budget because we’ve aggressively pursued other sources of funding, but we need to do more to convince our public funders that universities are worth supporting.

We were successful in getting more federal funding to support graduate students last year, but we still have a long way to go to ensure adequate funding for all our exceptional researchers and students.

What are you most proud of?

There are so many things. I’m immensely proud of our response to COVID-19.

And I’m proud of the progress we are making on Truth and Reconciliation — we have substantially strengthened both Indigenous teaching and research programs, including a new graduate program.

And I’m very proud of the progress we have made in addressing support of Black students and faculty. Support for the call to hire a cohort of Black faculty was overwhelming and we have been able to create an impressive core of Black faculty, and to attract and support more Black students through programs like the Black Student Success Centre.

Another remarkable achievement is the creation of the Wilson College for Leadership and Civic Engagement. It’s the only undergraduate program in the country where students from all faculties can develop the historical and societal awareness that are the hallmarks of great leaders. It’s a measure of the remarkable support we have had from loyal alumni and donors like Lynton “Red” Wilson.

I’m also proud of our support for entrepreneurship. Early in my time as provost, a chemistry faculty member, John Valliant, came to see me about using a medical isotope to treat cancerous tumours that would irradiate the tumor in situ without damaging surrounding tissue.

He needed time to spin off his company and basically wanted to become an entrepreneurial professor. We didn’t have a position like this in our structures, so the Dean of Science, Maureen MacDonald, and I ended up creating a position that would provide him with teaching relief while he focused on building his company.

That turned out to be a very interesting way to support a faculty member who was commercializing their research.

He spun off the company, and it incubated and grew in the McMaster Innovation Park. Then, last year, AstraZeneca bought it for $2 billion US.

So that’s the kind of innovation I was interested in supporting, and a great example of how researchers can take their ideas and move them forward in ways that have a major impact on our society and on our world.

How do you think McMaster has changed over the five years of your presidency?

I think we have a very strong senior team of vice-presidents and deans who really talk to each other and collaborate.

When I came to Mac, there wasn’t a huge interaction between the academic side and the administrative side of the university, and I think that’s changed in a significant way.

The colleagues around me have really driven it, and I think the university is incredibly well supported now.

I think there’s also a real sense of urgency in much of the teaching and research we’re doing. Some of the catastrophes that were once the stuff of science fiction are now upon us — pandemics, the wildfires, droughts and extreme weather events brought on by climate change, the rapid advances in artificial intelligence that are outstripping our structures for oversight and control, increasingly challenging geopolitical events.

When I talk to students and researchers across the university, I get the sense the people want to move quickly to use our evidence-based approach and leadership skills to solve these pressing problems.

What insights have you gained over the past five and half years?

Academic leadership is not a solo journey, and we make the best decisions when we act as a team.

It takes a bit more time to hear all the perspectives and gather many viewpoints, but the decisions we’ve made have been vastly improved by hearing input from many people.

I’ve also learned that for me personally, there is a time limit to leadership. There is no off-switch for a university president — you’re always thinking about the next challenge or opportunity or issue, even when you’re not physically at work. It’s a very demanding role and one you need to be ready to hand over when the time comes.

What are some of the things you’ve started and would like to see grow over time?

There are countless areas. I would really like the university to be an example of a sustainable community in a holistic sense. We’ve set a goal to be carbon zero by 2050.

At its core, this would be based on generating electricity using a small modular reactor, a combination of renewables and using heat transfer through a district energy approach. I am very excited about using McMaster’s campus to demonstrate how communities can quickly become carbon-free, and I hope we can continue to make progress on this goal.

I’m sorry I won’t be here to help lead the next fundraising campaign, but I will be contributing to that in any way I can.

We have a great story to tell about McMaster — our incredible students and our groundbreaking research — and I’m really optimistic about our campaign goals.

We established Global Nexus during COVID-19, and it has grown into a health innovation accelerator to encourage collaboration between researchers, public health, industry and government.

We’ve already had great success with McMaster’s inhaled vaccine and pandemic preparedness, and I know this growing ecosystem is the quickest way to get our discoveries out to the world. I hope it will continue to attract major support.

You’ve talked about returning to your roots as a researcher. Tell me about your plans.

I’m looking forward to some down time, especially with our grandchildren. And my dog.

Starting in the fall, I’ll be back in the chemistry department where I have space in a lab, and I’ll be getting back to more regular work with my research collaborators on projects related to sustainable building materials.

Tell me a bit about the research you’ll be focusing on.

We’re working on a project that takes CO2 and converts it into carbonates, which are basically small rocks that can be used in building materials.

This came about from a very interesting experiment with a company that isolates salt from salt flats in Sicily, where they allow the ponds to evaporate. Then they harvest the salt and end up with this brine at the end that’s highly caustic and needs to be neutralized; there’s a way to get CO2 to bubble through that and make carbonates.

It turns out there are a lot of similarities between what we see in the salt flats in Italy and what we see in the tailing ponds in the Alberta oil sands, so we’ve had some conversations about bringing our project to Canada to see if it will work.

What are you going miss about being president?

The people. I’ll miss the deeply committed colleagues who’ve served in leadership with me. I’ll miss the opportunities to meet with researchers doing incredible work and I’ll miss the conversations I’ve had with hundreds of inspiring students who are determined to make substantial contributions to global challenges.

And I’ll miss the excitement of seeing transformation happen — knowing what you want to do, working with the people who can help you do it, and then seeing change happen. For me, that’s been the greatest joy.