Indigenous voices come together at MIRI symposium

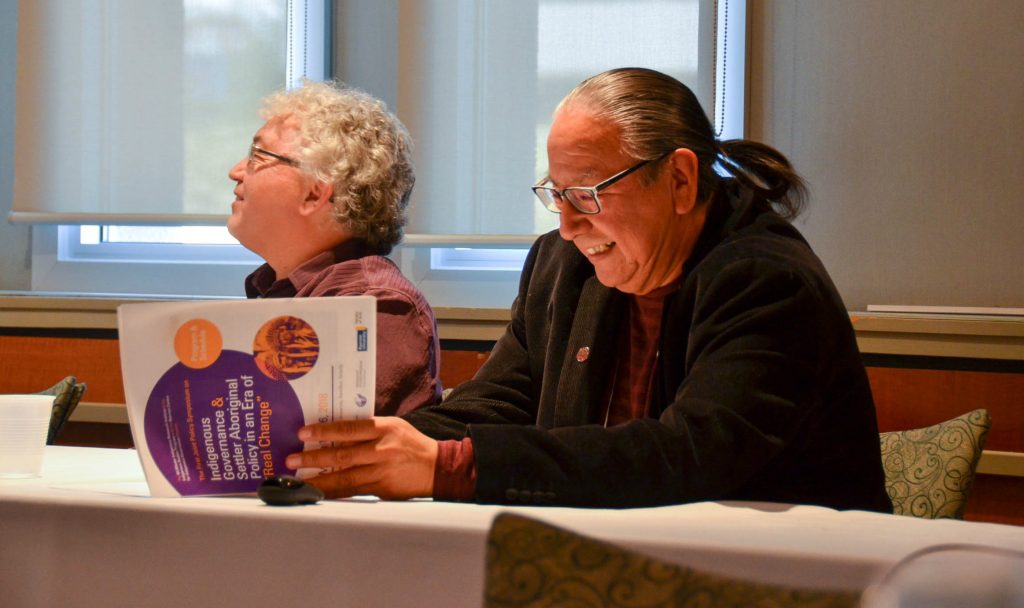

Tim Thompson, left, and Amos Key Jr. at a panel discussion on Indigenous languages at the MIRI symposium in March 2018

When McMaster’s Indigenous Research Institute (MIRI) was established in the summer of 2016, its acting director at the time, Chelsea Gabel, and Hayden King, her counterpart at Ryerson University’s Centre for Indigenous Governance, started talking about organizing a gathering focused on Indigenous policy.

Last week, the plan came together: The two institutions brought together dozens of community members and experts on Indigenous issues at McMaster for the joint Symposium on Indigenous Governance and Settler Aboriginal Policy in an Era of “Real Change.”

“The idea was to call together a gathering of Indigenous scholars and community members involved in various capacities around First Nations, Métis and Inuit issues,” says Rick Monture, acting director of MIRI.

With eight wide-ranging panel discussions over two intensive days, the symposium featured leading Indigenous voices from across the country speaking on issues related to the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) inquiry, the child welfare system and its link to incarceration, language revitalization, identity, rights, and governance.

Day 1 focused on political and legal matters, including self-government, Indigenous identity and citizenship, the implications of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, and the effects of making — and breaking — treaties.

The panel discussions on Day 2 focused on social policy issues, such as language revitalization —the Six Nations of the Grand River is home to the last surviving speakers of Cayuga — and stirring sessions on the MMIWG inquiry and the over-representation of Indigenous children apprehended into the child welfare system.

Every one of these topics had twin threads of identity and history running through it, but there was also a specific panel discussion on Indigenous citizenship, which mapped out a new and growing problem: Speaker Darryl Leroux explained how non-Indigenous people in parts of the country are increasingly taking up Indigenous identities, then working from within to influence land issues in ways counter to Indigenous interests.

“The gathering gave us a chance to get talking about the big things we all have to take on,” Monture explains.

Besides the scholars and community members in attendance, a large number of students turned out.

“We were glad to see it. We want to bring younger people into the conversation,” Monture says. “There’s a lot more understanding now that academic and community concerns can intersect. We can work together toward sorting these things out.”

According to Monture, McMaster was known to be a place where community would work with academics to advance Indigenous concerns even before MIRI was established. As far back as 1989, when Indigenous issues were brought to the university’s attention, staff and faculty and allies here worked to address them.

Now, with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report making it clear how important it is to pay attention to Indigenous concerns, McMaster is doing even more, Monture points out. University president Patrick Deane attended part of the joint symposium, and remarked on the energy and engagement at the event, even late on a Friday afternoon.

The response to the symposium and the level of engagement was overwhelmingly positive, Monture agrees. Both days quickly booked up and organizers had to start a waiting list, although Monture says they did try to squeeze everyone in who was interested. Organizers are already talking about the next symposium, in two years.

“We’re very pleased with the things that came out of it — the networking, the collaborations, the students who came, the community members who came,” says Monture. “People came away with a better understanding and appreciation of the work we do.”