Finding Hazel

In 1918, a 15-year-old girl named Hazel Layden died in the influenza pandemic that swept the globe toward the end of the First World War.

She was buried in Grove Cemetery, just a few blocks from Dundas Central Public School, where she had been a student.

Her memory might have faded into obscurity – just one of up to 50,000 Canadian victims of the deadliest pandemic in recent history.

A hundred years later, Robert Bell, a grade 5/6 teacher at what is now Dundas Central Elementary School, decided to teach a unit on the 1918 pandemic – and when he went to the Dundas Museum and Archives to look up materials for his unit, he found out about Hazel.

“That changed everything – finding out that a student who had sat in our classroom was so deeply affected by this pandemic made it deeply personal for the students and for me,” Bell explains. “It literally brought it home to them.”

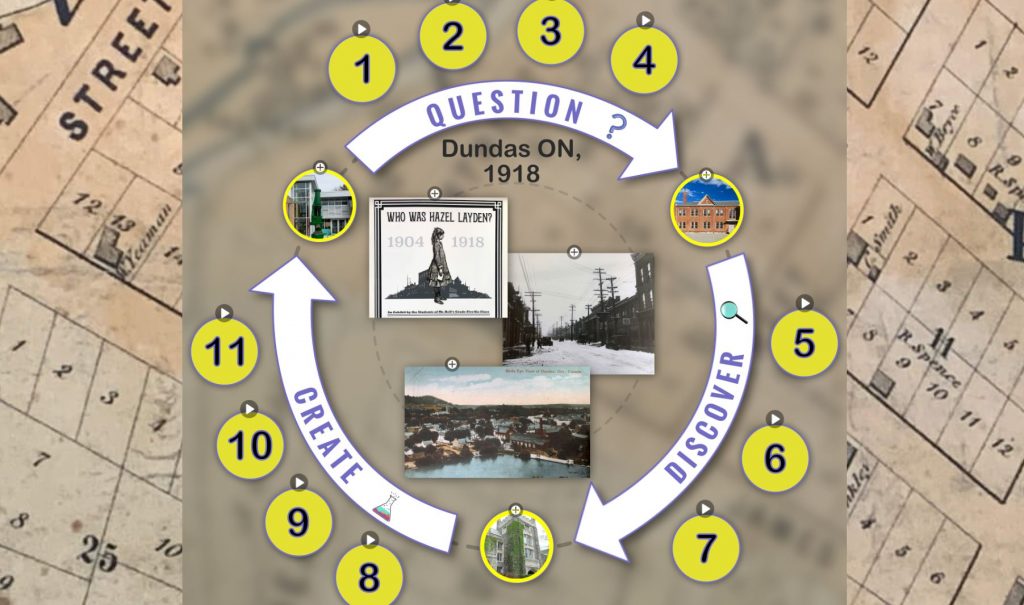

What had started out as a traditional social studies unit quickly turned into the Hazel Project, a massive study in collaborative learning, primary source research and digital communication.

Bell partnered with the McMaster Child and Youth University, a community initiative at Mac that brings families on to campus for kid-friendly lectures and sends student facilitators into schools to run interactive workshops. McMaster students came in to teach Bell’s students about the biology and epidemiology of the flu, as well as to help the students create videos and an interactive website that summarized the entire project.

And, as is typical with MCYU programs, the learning went two ways, says Sandeep Raha, director of MCYU and an associate professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Health Sciences.

“McMaster students taught the kids from the elementary school about the biology of the flu, how the flu works and how it spreads, and the kids from the elementary school taught our McMaster students about the history of the flu in Dundas,” says Raha.

“Our McMaster students were better able to appreciate the value of the science in the context of the history.”

Along with the digital aspects of the project, Bell’s students also worked with the Dundas Museum and Archives, Knox Presbyterian Church, where Hazel’s family were parishioners, and local historian Stan Nowak, who took the students to find Hazel’s grave.

“We kept finding artifacts or leads – it was like we were solving or uncovering a mystery,” says Bell. “Of course, in the background of all this we were very aware that we were discovering things about a child who had died – so as we got excited about our discoveries, we had to temper and sober our responses to the reality that we were exploring.”

The project culminated in the launch of an exhibit at the Dundas Museum about Hazel’s life, featuring artifacts that included the Dundas Public School roster with Hazel’s name on it, a photo of the class she would have been in if she had lived, and a match holder that her father had made. The exhibit was also an opportunity to bring together two branches of Hazel’s descendants who live in Dundas but weren’t aware of their common ancestor.

“This was a really cool project because I love history, so it was awesome for me,” says Izzy, one of Bell’s students. “It was a way even for kids who don’t really like history to enjoy it, because we all had a part of it. Most of us are from this town, and we could say, ‘Hey, Hazel walked on this floor, and now I’m walking here.’ That was neat.”

While the exhibit has now wrapped up, the Hazel Project has found a life beyond Dundas. The class’s interactive website recently received a national award from Defining Moments Canada, a heritage organization that promotes digital storytelling in history.

The contest, called Recovering Canada, accepted submissions about the 1918 influenza pandemic from schools, heritage communities, museums and universities from across Canada. Because they didn’t have a category for collaborative projects, though, the Hazel Project was judged alongside entries from museums across the country – and won first prize.

Ultimately, though, it all comes back to Hazel.

Up in the attic of Dundas Central, there are names scrawled on the beams, of kids who attended the school back to 1857.

Hazel’s name isn’t there. But the class has written her name and their own on a plaque, and they’re going to nail that plaque to the attic joists, joining the ghosts of more than 150 years of students.

“We were all here for a girl who died a hundred years ago,” says Bell. “That’s what drew us all together. You think about a life, and a life ending – but the story of a life doesn’t end when that life does.”