‘Education is impossible outside of society, just as society is impossible without education’

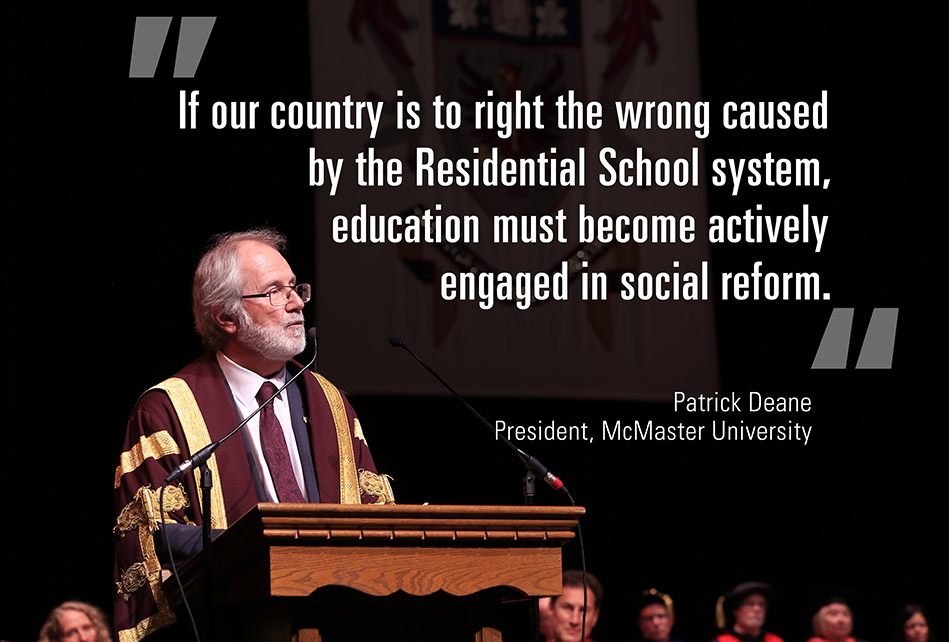

On June 21 – National Aboriginal Day – we look back at last week’s Convocation address given by President Patrick Deane, who touched on a number of topics in his speech, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report.

I want to underline something essential about the education you have received here at McMaster, and about education in general: learning is a profoundly social activity. We learn by dialogue with others, whether the interaction is electronic or through the pages of a textbook, whether the other party in the dialogue exists as a professor, a mentor, a classmate or a character in a novel.

Education is impossible outside of society, just as society is impossible without education. The American philosopher and education reformer John Dewey made the point more than a century ago, beginning with a simple declaration: “I believe that the school is primarily a social institution.”

Dewey’s Progressive Education Movement held that education is not simply a social activity, but also the agent of social reform. Dewey argued that the education system at the time failed to recognize the school as a form of community life. Instead, “It conceives the school as a place where certain information is to be given, where certain lessons are to be learned, or where certain habits are to be formed. The value of these is conceived as lying largely in the remote future—the child must do these things for the sake of something else he is to do; they are mere preparation. As a result they do not become a part of life experience of the child and so are not truly educative.”

“True” education for Dewey is not preparation for life, but life itself: the driver of human progress, and the critical means by which society is made and continually re-made.

Dewey articulated this in 1897, in a document called “My Pedagogic Creed,” which is still relevant today. Universities continue to insist that their mandate is not simply to provide vocational training but to educate citizens to shape society. So it is no coincidence that Dewey is heavily cited in a 2013 report to the European Commission, which seeks to re-imagine postsecondary education on humanistic principles, and by so doing contribute to Europe’s social and economic renewal.

Education may be a powerful agent of social re-formation, but if it only reinforces an existing framework, it becomes the enemy of progress and reform. Fifty years of Apartheid in South Africa was facilitated by formidable police and military forces inside the country, of course, but education was the real and most effective tool of oppression. That is why the Soweto riots of 1976 started with schoolchildren protesting against the language of instruction.

Here in Canada the legacy of the Residential Schools system has also proven how the power of education can be turned to destructive purposes—to advance the cultural hegemony and political control of one group over another. Society made homogenous through suppression, extermination or assimilation is not society as Dewey imagined it, nor is this a model that can be called education in any real sense. It is forced acculturation, using the apparatus of education.

Interestingly, the genesis of Canada’s Residential Schools system coincides historically with the emergence of the Progressive Education movement south of the border. The Mohawk Indian Residential School opened in Brantford in 1831, but it was in the latter half of the 19th Century that the system took shape and the policy that drove it became apparent. After the Constitution Act of 1867, Canada formally adopted a policy of assimilation, and the Nicholas Flood Davin Report 12 years later declared, in language that is still shocking, that “the aim of education is to destroy the Indian.”

Duncan Campbell Scott, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Canadian Government from 1913 to 1932, spoke of the need to “get rid of the Indian problem,” continuing the process of acculturation “until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department….” In 1920, Scott drafted an amendment to the Indian Act making it mandatory for all native children between seven and 15 to attend school, attendance at residential schools becoming compulsory.

This curious contrast shows that even where there is a consensus that education has the power to shape society, it does not follow that the inevitable outcome of education is democracy, enlightenment and the realization of human potential.

If our country is to right the wrong caused by the Residential School system and evolve as it should, education must be returned to its Deweyesque purpose and become actively engaged in social reform. It must work to bring us all into what might be called a “commonwealth” of knowledge—infinitely rich and complex, admitting diverse perspectives and epistemologies, because of the infinite richness and complexity of society.

It is little wonder so many of the Calls to Action in the 2015 Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada directly address education. Six seek to redress the immediate legacy of the residential schools by reforming the funding and administration of education for Indigenous young people, and counteracting the alienation of students from their heritage.

Many others address the need to educate non-Indigenous Canadians about Indigenous issues, especially those in public roles, whose own education, whether they know it or not, gives them power to shape our society. Thus doctors, nurses, journalists and lawyers are all enjoined to acquire the intercultural competency to make them active agents of a new Canada founded not on exclusivity, coercion and force, but on inclusivity. As Indigenous educator Roberta Jamieson recently noted in The Toronto Star, “to make reconciliation work, non-indigenous Canadians will have to invest time.”

It is a scandal that for nearly a century our country turned education to the diabolical purpose of “destroying the Indian”. For all who cherish their work as educators this is cause for indignation, great grief and regret. But today is a moment of great promise. You have been nurtured at McMaster in a tradition of progressive education. You have acquired not just the information necessary to perform a particular task valuable to our economy, but knowledge and wisdom derived more broadly from our communal life and therefore potentially transformative of our society.

Graduates, the point of celebrating your success as we have done today is to underline the extent to which your individual achievements are also social achievements. This is a communal event because the meaning, quality and richness of our life together on this planet is ultimately the point of education.

For that reason, this physical place is highly significant; it is literally the ground of our coming-together and the emblem of our deeper commonality, kinship and shared aspirations. We have decorated it with the iconography of a culture many of us share, yet our obligation as educators must be to grow in dialogue with other iconographies and histories—not blindly, indiscriminately or sentimentally, but as thinking, feeling, complete human beings. Education thrives on the sheer abundance of our existence.

I will end where at future convocations I intend us to start—by recognizing and acknowledging that we meet on the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations, and within the lands protected by the “Dish With One Spoon” wampum agreement. To say that is to acknowledge a debt to those who were here before us, and also to speak against those teachers, clerical and secular, whose project over nearly a century, was to alienate peoples from their history and culture and to make of the educational process the antithesis of what it ought to have been.

I could not be more proud to stand with you in this meeting place, pondering what—moving on from here—you will be able to do with our society and our world.