Some disassembly required: Department dedicates heart of a retired superconducting magnet to David Farrar

'It doesn’t get better than this.' President David Farrar, seen here with Bob Berno, speaks of his experiences using a spectrometer in the 1970s. The department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology dedicated the carefully cross-cut superconducting magnet to Farrar in recognition of the end of his tenure as university president.

Bob Berno tried hard, but couldn’t find any takers for a 39-year-old magnet that stood two metres high and weighed hundreds of kilograms.

The 4.7 Tesla superconducting magnet had been the heart of a 200MHz nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer at McMaster, where generations of undergraduates and researchers had used the scientific instrument to analyze chemical compounds.

Built in 1986 and first used by Ontario Hydro, the spectrometer made its way to McMaster in the late 1990s.

In 2002, it was moved to an undergraduate teaching lab in the Arthur Bourns Building. Thanks to a console upgrade, the spectrometer recorded high quality data for another 20 years.

“For many chemistry undergrads, that workhorse spectrometer was their first introduction to using this powerful chemistry tool,” says Berno, who’s responsible for maintaining eight NMR spectrometers as manager of McMaster’s NMR Facility.

The time had finally come a couple years ago to retire the workhorse and replace it with a sleeker and smaller benchtop version with modern features and functions.

Berno found a home for the defunct spectrometer’s electronics but no one wanted the massive magnet. Shipping it off to the scrapyard felt like a waste but seemed to be the only option.

Berno first needed to get the magnet out of the lab so he reached out to Jim Cleaver in the Engineering Shop.

Cleaver and his team knew how to move large, heavy and fragile equipment out of tight spaces. He said he’d move the magnet and temporarily store it until Berno figured out how to get rid of it.

That bought Berno some time to come up with a plan. He knew that students and researchers using spectrometers often wondered how they worked. “All of us are kids at heart.”

Berno found posts online of magnet cross-sections, sometimes done successfully and often times not.

The magnets are like Russian nesting dolls — “concentric cans within cans wrapped in insulation” explains Berno.

Taking a blowtorch to the magnet’s outer layer would damage the inner layers — it would take precision work by skilled hands.

Berno asked Cleaver if he was up to the challenge of slicing open the magnet to reveal its inner workings.

“Bob didn’t want the magnet to go into the dumpster,” says Cleaver. “I thought it was a cool thing to save so we decided to give it a try. It took longer than we thought.”

The shop had the tools and the talent to disassemble the magnet, hoists to lift and move the heavy pieces, blades to cut cross-sections out of the individual pieces and the patience to reassemble it.

They started out by working off a couple of photos Berno had downloaded from the internet but then a co-op student in the shop found instructions on how that exact model of spectrometer had been put together.

As a fellow tradesperson, Cleaver was impressed by the quality of work that had gone into assembling the magnet.

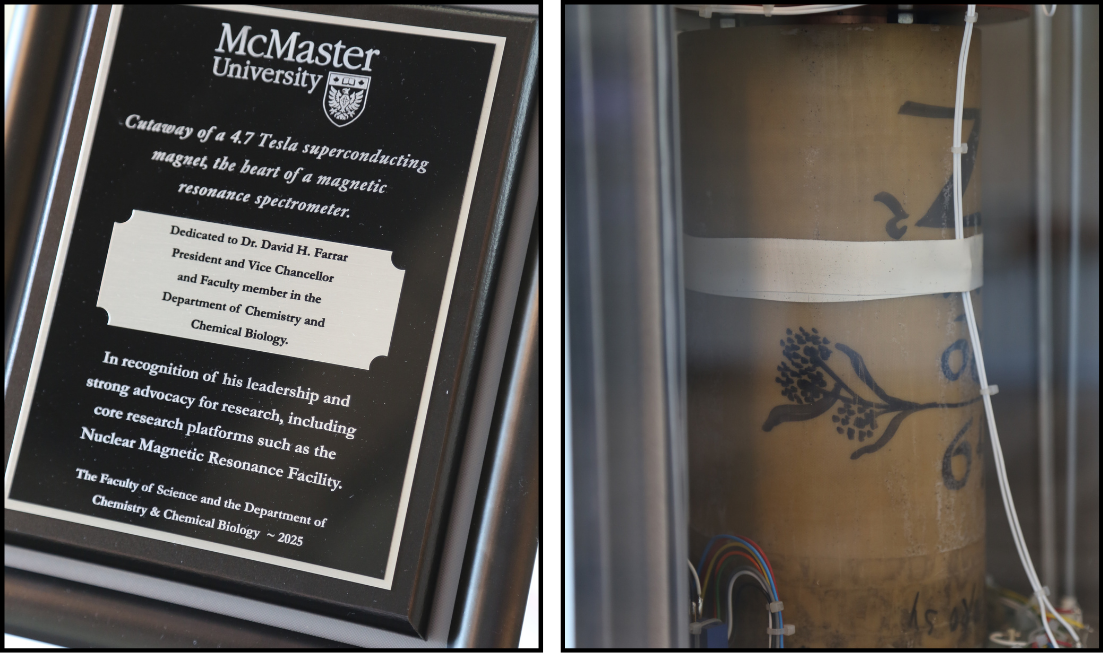

The engineers who assembled the magnet also had an artistic flair — they had drawn a flower on the solenoid coil, knowing it would likely never be seen. Berno’s tried to find out who drew it but the clandestine artist’s identity remains a mystery.

Berno wanted to publicly display the cross-cut magnet in a high-traffic area. Parking it in the ABB foyer next to the Elements at McMaster interactive periodic table seemed like the perfect spot.

While he usually begs forgiveness rather than ask for permission, Berno thought he should first pitch the idea to Gillian Goward, who was then the chair of the Chemistry and Chemical Biology department and is now the Faculty of Science’s Associate Dean of Research.

Goward not only agreed on the location, she thought it would make the perfect gift for President David Farrar, who had just announced his decision to conclude his tenure at the end of his five-year term and return to his roots as a researcher.

Farrar is a chemist and will continue to hold a faculty appointment in the department.

The magnet was unveiled last week at a dedication ceremony with a plaque recognizing Farrar’s support for research, including core facilities like the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Facility.

“It doesn’t get better than this,” Farrar said at the unveiling.

He told the audience of students, faculty and staff about first using a spectrometer back in 1972.

Berno is glad the old magnet has a new life as a repurposed teaching tool, says Berno.

“For researchers who’ve ever wondered about the hidden forces that let spectrometers unravel molecular mysteries, all’s been revealed thanks to Jim and the team in the Engineering Shop. It’s definitely worth a visit.”