A McMaster program is taking post-secondary classes inside prison walls

Through the national Walls to Bridges program, McMaster's Indigenous Studies department is taking students into a federal correctional facility, where incarcerated and non-incarcerated students earn university credits and challenge expectations.

Madelaine Lamarche remembers how nervous she was the first time she went to class in a prison setting.

“My expectations for the prison were very stereotypical,” admits Lamarche, a McMaster student who is part of Walls To Bridges (W2B), a national program that moves university classes into prisons, so incarcerated and non-incarcerated students can earn university credits while taking courses together.

“I had a lot of biases from TV, so I expected all of these metal detectors and being patted down and everything, and that was totally not it like how it was,” Lamarche says. “They were very, very nice.”

The Indigenous Resurgence class at Grand Valley Institution for Women (GVI) dismantled her mental walls, Lamarche says, and challenged her expectations.

Breaking down barriers between incarcerated and non-incarcerated students is one of the goals of the W2B program, in addition to providing academic credit, says facilitator and McMaster PhD student Sara Howdle.

“Walls to Bridges allows students and facilitators to practise non-hierarchical learning and challenges our perceptions of incarceration and justice,” says Howdle.

“The methods we use encourage anti-colonial pathways of relating to each other and participatory action. It’s a unique experience for everyone involved.”

W2B’s new national director, McMaster professor Savage Bear, is overseeing the program’s relocation to McMaster from Wilfrid Laurier University.

The program has taken two Indigenous Studies courses to GVI so far, with Indigenous Arts and Culture currently wrapping up.

We spoke to incarcerated and non-incarcerated students, GVI’s chief of education and Bear about the program, how it can reduce recidivism rates and create bridges between those inside and outside the prison walls.

Peter, GVI’s chief of education

Peter Stuart never expected to teach in a jail.

“It seemed like I would be working with people who really did not want to be there,” the former middle school teacher says.

But he really needed a job, so when one came up at GVI, “I just took it.”

His first day, the first person he met asked what he was there to teach.

“I told her I taught English and math and she said, ‘That’s great. I need my math to finish my high school and I want to finish my high school.’ ”

“So from the very first person I met, I realized that these were motivated students. I’ve been here for 17 years and I still see that to this day.”

Most of the students at GVI did well in school before dropping out, often after getting pregnant, says Stuart, now chief of education. Most tried to go back to school, but work and family often got in the way. And even if they did get high school education at GVI, there was little higher education available.

Until W2B got in touch.

“They said, ‘We have this program. It involves the university coming in. Half the students are from the community. Half the students are yours, and the university’s going pay for it. Would you be OK with this?’ And I just said, ‘Of course!’

“Why would anybody possibly not want that? At the very least, even if it wasn’t furthering their education towards a specific credential, it was opening their minds and keeping their minds busy and vibrant.”

The first class was “extremely popular,” with 34 applicants for 10 spaces. Now there are two or three classes in GVI every year.

Thanks to the efforts of the teams at GVI and W2B, around 17 per cent of residents are in post-secondary classes, compared to the federal average of 1 per cent, Stuart says.

He starts laying out the numbers to show why that figure matters: There’s a 70- to 100-per-cent decrease in reoffending rates among those who earn a post-secondary credential. Every dollar spent on education in correctional services results in $6.37 in direct savings because students were less likely to come back. Fewer crimes are committed, there are better long-term outcomes for the families of residents.

The list goes on.

While the numbers paint a picture of the program’s success, it’s the individual stories that drive home the impact.

Stuart interrupted this interview to answer a knock at the door from a W2B student who is writing a paper for the Journal of Prisons. Another student is now pursuing a PhD, with a supervisor she met through W2B.

And then there’s Denise.

Denise, the former GVI resident

Denise Edwards was always interested in education and learning, but never fit in at school, never found those spaces welcoming.

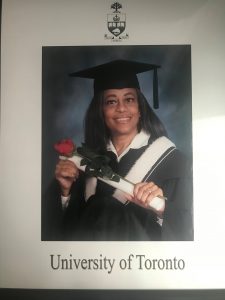

But while she was at GVI, Edwards took five courses, reigniting her passion for education and starting her on the path to completing an undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto, double majoring in Caribbean History and Equity Studies.

The W2B courses gave her space to flourish academically, she says. Gone were the stuffy classrooms, the institutional barriers that prevented those with intersectional identities from succeeding.

Instead, she found non-hierarchical courses, with chairs arranged in a circle with everyone encouraged to contribute to deep conversations that were reluctantly broken off when the lessons ended.

“It’s transformative, it really is,” said Edwards. “It’s put me on a path where I did not think that I would be.”

She even found herself leading her peers at U of T, offering to rearrange classrooms into the round configuration, and encouraging classmates to read Caribbean history so they could master their understanding of European and colonial history.

Savage Bear, the national director

Savage Bear, assistant professor of Indigenous Studies at McMaster, is the National Director of the W2B program.

Back when she was teaching at the University of Alberta, a student told her that their favourite class was Inside Out, the U.S. equivalent of W2B. Bear signed up for training that same day, then joined the W2B program.

When Bear came to McMaster, the school agreed to set up its own W2B program. Bear has seen first-hand the impact it has on students at the university and in the prisons.

“It is truly building bridges,” she said. “Everyone is so intellectually stimulated. Can you imagine the conversations we have?”

And the results speak for themselves, with students continuing their education after the courses.

“I’ve had students who I met in the Edmonton Institution for Women who came out and went on to get degrees at the University of Alberta.”

That’s especially important, as a lot of the Indigenous students (who are disproportionately represented in the prison system) are the first in their families to get higher education.

“It’s my life’s goal that if people want to get into higher education,” says Bear, “then I’m going to pave the way.”

For Lamarche, the class was not without its challenges — the threat of prison lockdowns was ever present — but she was thrilled with it.

“It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity,” she says. “Even if you’re somebody who just wants to go into business, for instance, I would recommend it.

“It really is an eye-opening experience and it really teaches you to not judge anybody.”