Inspiring Indigenous internationalism

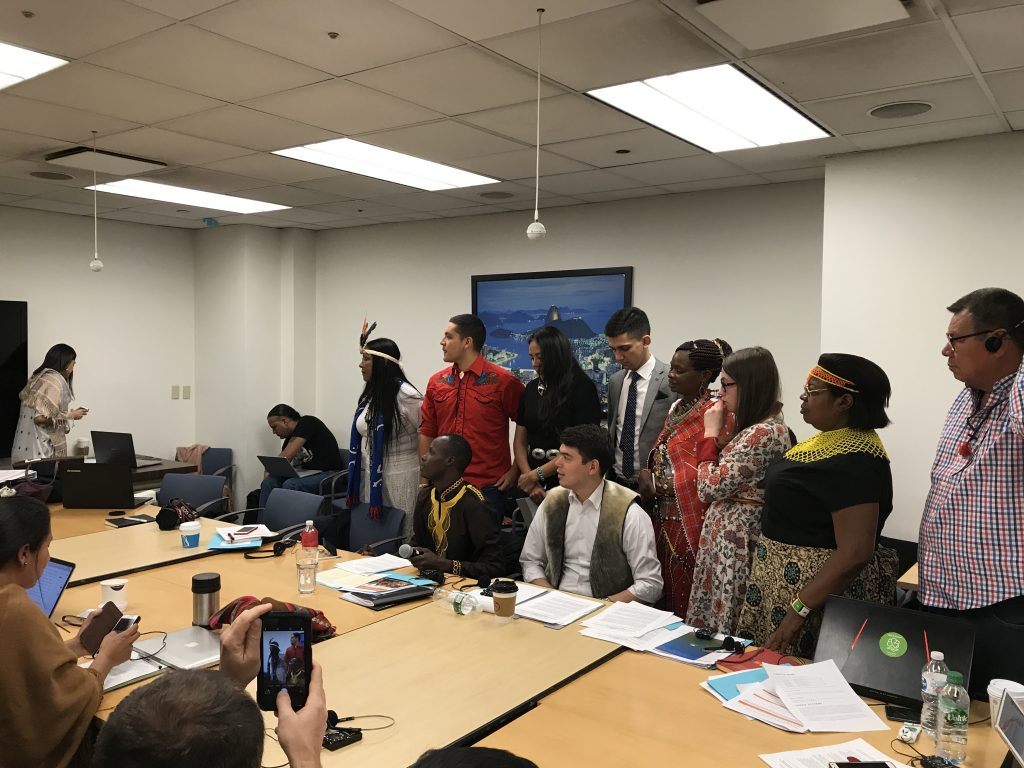

Project Access trainees represented the 7 recognized Indigenous regions of the world, facilitated by the Tribal Link Foundation at the UN Development Program in New York, NY.

Piers Kreps graduated from McMaster’s political science program in the Faculty of Social Sciences in the spring of 2018. He writes about his experience attending the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and shares his insights.

My desire to reconnect with my people, engage with Indigenous peoples from around the world, and love of political discourse led me to attend a unique training for Indigenous peoples called Project Access. This program is offered by the Tribal Link Foundation in New York City. What follows is an account of my experience at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, how I got there, and the lessons I learned.

How I got here:

I grew up outside my home community of Tuktoyaktuk, which lies on the Arctic Ocean 150 km north of Inuvik in the Northwest Territories. When I was five years old, my dad took my sister and I to Toronto. Since then, I’ve lived, grown, and been accustomed to life in the south, graduating from high school and university. Unmotivated by introductory courses, I took a brief hiatus and found myself working in the field of Sport for Development at Right To Play. This gave me the opportunity to reconnect with Indigenous communities across the country. Prior to that, I had been ashamed of my heritage but that experience motivated me to go back to school [at McMaster] and complete my degree. My desire to get involved in international Indigenous politics began during a unique community exchange with Indigenous Water Rights Activists in Gisborne, New Zealand (Aotearoa), complimenting an experiential learning class with Dr. Dawn Martin-Hill of Indigenous Studies. Following our trip to New Zealand, we reconnected with Maori and supported their statements (or interventions, in United Nations (UN) lingo) at the UN Ocean Conference in New York City. There, I was able to connect with Tribal Link Executive Director, Pamela Kraft; who invited me to the Project Access training.

Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations

Indigenous peoples have been active on the international stage for decades. The first major appearance on the global stage was by Haudenosaunee Chief Deskaheh (Cayuga, Six Nations); who traveled to Geneva in 1923 to seek recognition from the League of Nations. The League dissolved and the world descended to world war. The push for Indigenous involvement in international politics resurged in the mid 1970s and onwards, including: international UN-commissioned studies, an International Decade of Indigenous Peoples, and the creation of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UN PFII); the Forum which I attended. The forum is an annual event that takes place at the UN headquarters in New York City the last two weeks of April. It provides our people with an opportunity to influence various agencies within the UN network. NYC is also a convenient and accessible location for Indigenous groups from all over the world.

As an Inuk, my people (Inuit) reside in four ‘host states’: Russia, USA, Canada, and Greenland (Denmark). This factor has motivated me to get involved in international politics. Borders, as they are seen [and created] by western constructs, did not traditionally exist to Inuit. As a result, our rights often vary as we cross borders. The Inuit experience in Greenland is different than in Canada, as our parliaments view our rights as Inuit differently. What drives us as Indigenous peoples to the international stage is the desire to advocate for our rights as a collective.

So where do I go?

The Permanent Forum, as it is often referred to, serves as an advisory body to the United Nations Economic and Social Council (UN ECOSOC). While the UN serves nation-states, the UN PFII provides Indigenous peoples with a unique avenue to voice concerns in an influential setting. However, navigating the UN is complex and often intimidating for many people, and that’s where Project Access shines.

Project Access was established by the Tribal Link Organization to help Indigenous peoples understand the mandate of the UN Permanent Forum. This year, the Project Access training brought together Indigenous leaders from all 7 of the Indigenous regions. The program is delivered with the aid of several UN accredited Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and most helpfully, with the help of previous participants who serve as mentors. The multifaceted training helps new participants understand the history of Indigenous peoples at the UN, the purpose of the Permanent Forum, and how to deliver effective interventions on the floor. Taking place for the three days preceding the UN PFII, the training brought in speakers from UN accredited Indigenous NGOs (International Indian Treaty Council), UN agencies (Convention on Biological Diversity), and academia (Elsa Stamatopoulou, Director, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Program, Columbia University). Furthermore, we were able to meet the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as the Chief of the Secretariat for the Permanent Forum!

The most beneficial facet of the training was our exposure and engagement with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP]. Adopted in 2007 by the UN General Assembly, this text serves as a framework for incorporating Indigenous rights into existing state legislations. As this text is constantly referred to in our communities, in the media, and in government, it was incredibly helpful to learn about the process and intent from some of its architects. For me, with a [very brief] background in development work, and interest in continuing in this field, development is only referred to in the UNDRIP considering political, social, and economic conditions in conjunction. This phrase could have tremendous implications when considered by government and corporations, again, in conjunction. As Indigenous peoples, we must ensure that developments strengthen our social and political standing, alongside our economic standing.

Community work

The UN is a great place to raise concerns and make recommendations to improve political, social, and economic conditions. There are several mechanisms available. However, the purpose is to serve as an arena for nation-states. Unfortunately, we as Indigenous peoples often find ourselves in dispute with nation-states. The big takeaway, and most important aspect of international work is to stay true to yourself and your people. The process of a successful UN PFII experience begins in your community, with the work you do – wherever and whatever that may be. You must arrive to the UN with a purpose that fits with the mandate of the Permanent Forum.

The plenary sessions at the UN are fantastic and several impactful interventions are delivered. However, I have found that during this forum, the side events are the best opportunities for connecting with similar peoples and organizations. The facilitators of side events apply to showcase the work they are doing, and connect participants and attendees to an extensive network of Indigenous communities and allied organizations around the world.

While the UN PFII provides Indigenous peoples around the globe with an avenue to raise awareness on pressing issues within our communities, the real work happens at home. As my advocacy work with NGOs and at McMaster thus far has shown me, community members are the real agents of change. Project Access has enabled me to use the Permanent Forum, work within the mandated areas of the PFII, and better understand the UNDRIP. But, the real benefit in this work happens when we take the tools and ideas we bring to the table to further inspire change, share strategies, and continue the momentum. Trainings like Project Access must be attended if at all possible (many UN affiliated trainings occur in various locations). Their facilitators and mentors ensure that you are prepared – time spent at the UN is challenging, but rewarding. They excel in bringing together people with similar experiences to work alongside one another, sharing different but equally valid perspectives.

I would like to recognize the efforts of Dr. Dawn Martin-Hill, who has been the ultimate mentor; and Dr. Henry Jacek, who awoke the political nerd in me. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Bernice Downey’s contribution, which allowed me to attend. I plan on continuing this work on the international stage, and will attend the London School of Economics and Political Science for a MSc, International Social and Public Policy, September 2018.