The mapmaker’s dilemma: How do you solve a problem like Crimea?

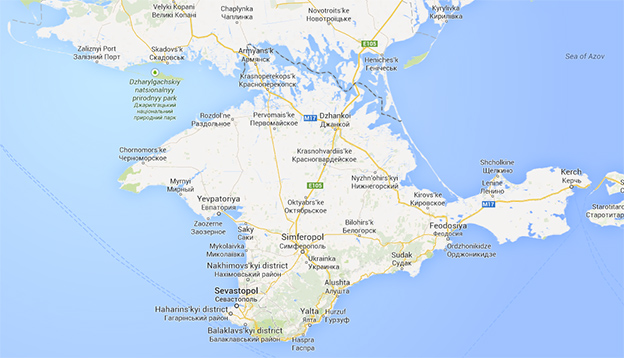

The region of Crimea, as shown to Canadian users on Google Maps. Note that Google depicts the border between Ukraine and Crimea as 'disputed' for international visitors. It shows Crimea as part of Russia for Russian users.

Most of the time, maps help you get from point A to point B. But when it comes to geopolitics, maps have long been used as much more than way finders.

Changes made recently to Google’s map of Russia – which now includes the disputed region of Crimea, at least for Russian users – bothered many observers. But they’re just the most recent (and digital) examples of political gamesmanship that has been played out on paper for hundreds of years.

And while these games might seem trivial, they’re very important to any information war.

“Changing the maps makes things seem official,” says geographer Walter Peace, McMaster’s map expert. “It’s also a way of promoting what you’ve done. More people will see the changes, and more people will accept this new, ‘official’ version.”

He points to turn-of-the-century maps of the British Empire as historical examples of maps with political purpose.

“George Parkin’s 1893 map puts Canada – the globe’s second-largest country and a large piece of the empire – at the centre of the world,” says Peace. “Because of this placement, if you look at the bottom corners of the map, you’ll see Australia and New Zealand twice, which sent the message that the British Empire truly went to the four corners of the world.”

It also helps that, despite the fact that they regularly change, most people see maps as authoritative.

“You can manipulate the characteristics of space – whether it’s the shapes of boundaries, where the boundaries are, etc. – and people will accept, without question, that the map is true. There’s just something ‘official’ about a map.”

Maps drawn before, during and after the First World War also present interesting case studies in manipulation for political purposes.

“How those maps look is going to change depending on where they were made and for what purpose,” says Peace.

Other mapping “mistakes” aren’t political at all, but help protect mapmakers’ copyright.

So-called “paper towns” are fictitious settlements – deliberately added but rarely acknowledged by publishers – placed on maps to help catch copyright violators.

One such example – the non-existent town of Agloe, New York – was in fact copied and continued to appear on maps until the 1990s. It even briefly became a real place after the opening of the Agloe General Store in the 1950s.

In a case of campus rivalry, the towns of “Beatosu” and “Goblu” were inserted into the 1978-1979 official state map of Michigan by a University of Michigan alumnus; the first a reference to beating rival Ohio State University, the second to the slogan “Go Blue!”

So why do we still care so much about map meddling?

“Our sense of identity is attached to the geography that we know – where we were born, where we grew up, what nation we belong to – and there’s a connection between people and what they see on a map. When someone comes along and alters that, it doesn’t quite feel right.”