Shooting for the moon: How William McCallion brought the stars to McMaster

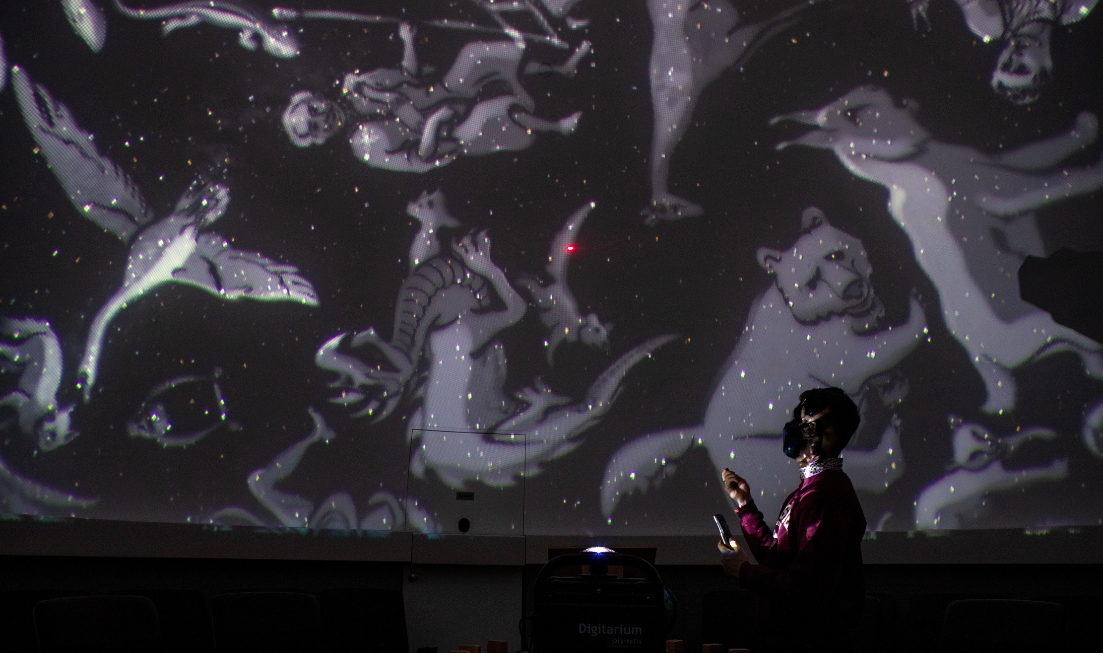

A graduate student explains constellations in the campus planetarium. In the 1950s, despite not having the funds, equipment, building space or seating for it, mathematician William McCallion systematically overcame every obstacle with creativity and grit to realize his idea of having a planetarium on campus.

“Let darkness come … stars are overhead.”

Six words in the 1998 obituary for professor emeritus William McCallion perfectly summed up his legacy at McMaster.

Not only was McCallion the driving force behind the university’s history-making planetarium, he delivered a record number of celestial tours.

In 1943, McCallion — who’d just graduated from McMaster with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics — became both a sessional lecturer with the university’s naval training program and a member of the Hamilton chapter of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

Six years later, the chapter’s 50 members committed to bringing a planetarium to Hamilton, similar to the one that had just opened at the Buffalo Museum of Science.

McCallion successfully lobbied the university to be the planetarium’s home. Harry Thode — at the time, principal of Hamilton College, and eventually president of the university — saw the planetarium as “a definite asset to the university and an aid in teaching astronomy.”

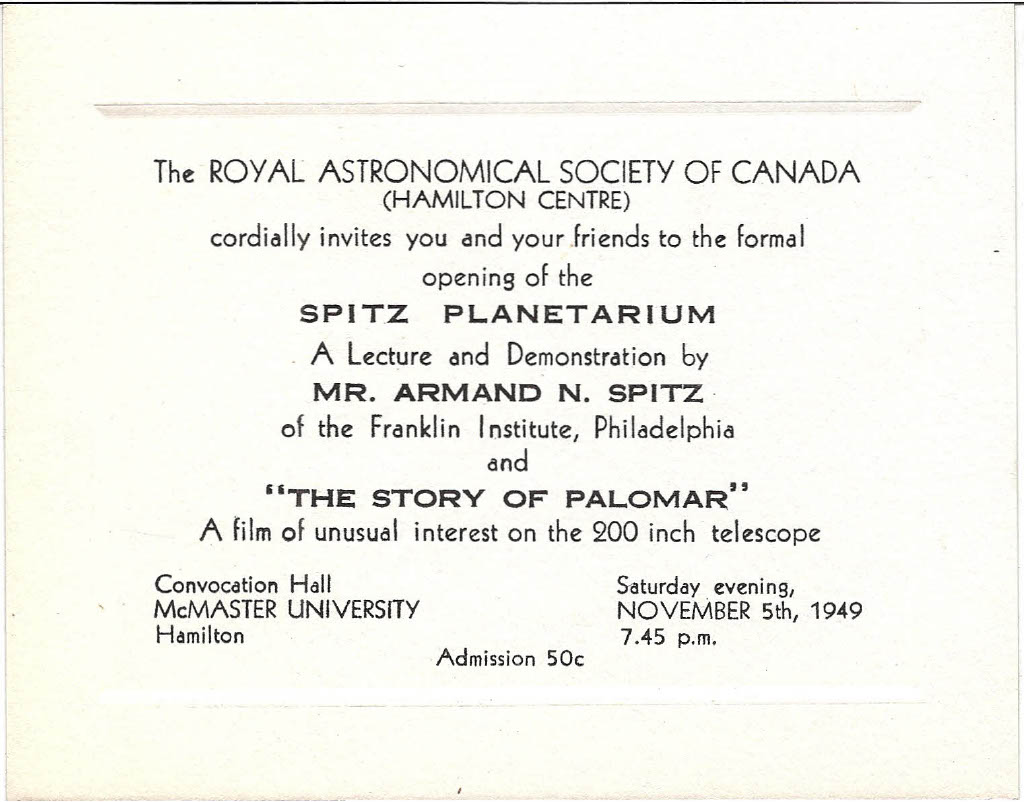

On Nov. 5, 1949, the Hamilton chapter presented McMaster with a Spitz planetarium projector. Tickets to the sold-out event in Convocation Hall (50 cents each) raised $125, part of a series of fundraisers to cover the projector’s $1,150 price tag.

The projector’s inventor, former newspaper reporter and science educator Armand Spitz, was the evening’s guest speaker.

McMaster became the first in Canada to use his state-of-the-art projector.

A few months later, McMaster’s planetarium again made history, becoming the first in Ontario to offer public tours of the stars.

At that point, the projector had a home but no dome.

With postwar student enrolment soaring, space was at a premium on campus — so converting a classroom into a permanent planetarium wasn’t an option.

McCallion enlisted the help of Evelyn Theodore Clarke, McMaster’s superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, to build a makeshift planetarium.

They designed a system for hanging an army surplus parachute umbrella-style from the ceiling in a Hamilton Hall classroom.

The price was right — only $20 — but it took more than three hours to move chairs in and out of the dome for a one-hour show.

There was one other problem — the classroom wasn’t “light-tight” so shows could only happen at night.

“This, of course, was a great handicap to teaching, since it was not easy to assemble students in the evenings for classes,” McCallion and Truman Norton wrote in the RASC Hamilton chapter’s August 1959 newsletter.

The parachute was retired in 1952 and replaced with another McCallion creation: Up to 60 people could sit inside his portable dome made of corrugated cardboard over a wooden frame. Converting a daytime classroom into a nighttime planetarium was now quicker and easier.

In the fall of 1954, the planetarium finally had a permanent home when the Physical Sciences Building opened.

McCallion and Clarke once again joined forces to design the dome in a custom-built, light-tight basement room. Shows could now run day and night for university, secondary and elementary school students, along with community and church groups.

But audiences had nowhere to sit: The planetarium’s budget ran out before 60 theatre-style seats could be bought and installed. So yet another fundraiser was launched with friends of the planetarium buying $25 chairs, complete with commemorative bronze plaques.

Not only did McCallion design three domes and help raise money, in the planetarium’s first decade, he delivered upward of 2,500 presentations to nearly 150,000 people as the director of public viewing.

He also took the projector on the road at least two dozen times. In 1959, he enlisted the help of Reverend Norman Green and William Sled from the RASC’s Hamilton chapter to keep up with the public demand for shows.

Looking back on the planetarium’s first decade, McCallion and Norton said it had delivered on its promise to be both a “valuable teaching aid for astronomy classes” and “a very excellent public relations instrument to make the university better known to the community.”

They hoped the success of the planetarium at McMaster would encourage more planetaria to open across Canada for “studying the stars without depending upon the stars.”

McCallion would go on to serve as director of Educational Services and dean of the School of Adult Education, retiring in 1978 and continuing as a mathematics professor until 1987. Five years later, the planetarium was named in his honour.

McCallion — who’d bravely met the challenges of living with Parkinson’s disease for 29 years — passed away on April 18, 1998 in his 80th year.

The W.J. McCallion Planetarium today hosts more than 300 public and private shows annually, created and delivered by graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and faculty in the Department of Physics & Astronomy.

McMaster also brings celestial tours to the community with a portable planetarium.