The life and legacy of trailblazer Lulu Gaiser

McMaster’s first female professor was an outspoken advocate for research and women in academia, and was the driving force behind McMaster's first research-focused greenhouse. A century later, the University is looking at ways to honour the Ivy-League educated, barrier-breaking, botanist.

A quick chat with historian Kristina Llewellyn about Lulu Gaiser turns into an hour-long conversation and walk around campus.

Llewellyn, who has a PhD in Educational Studies, is fascinated by Gaiser: In 1925, she was the first woman to join McMaster’s faculty; she went on to lead two departments and was the driving force behind the university’s first greenhouse. She also earned international acclaim for her pioneering early-career work on plant genetics.

A hundred years later, finding people on campus who’d recognize Gaiser’s name would be a challenge, Llewellyn notes.

“Dr. Gaiser’s a trailblazer who’s been lost to history,” she says. “It’s time to revisit and retell her story.”

‘So far ahead of the times’

Gaiser was raised on a farm in Huron County at the start of the 20th century. After graduating from Western University in 1916, she went to teacher’s college and a teaching job at her hometown school in Crediton, Ont., then at an experimental school for immigrant children in New York City.

“Women in the early 20th century weren’t meant to get an education for their own personal ambitions,” notes Llewellyn. “They earned a degree so they could be of future service to others.”

While women were going to university in growing numbers at the time, their opportunities were limited. Many became teachers and nurses, with the expectation that they’d quit their jobs once they got married and started a family.

Gaiser never married or had children. She went back to university, earning a master’s degree in plant pathology from Columbia University in 1921. She was a committed lecturer, according to students.

“(She) was a dramatic and colourful lecturer, who obviously loved her subject,” said a former student.

Before coming to McMaster in 1925, she worked in a research lab at Barnard College and at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C.

She completed a PhD in cytology, also from Columbia, while working at McMaster.

“Dr. Gaiser was so far ahead of the times,” says Llewellyn.

“Being a teacher was one thing. Becoming a researcher and competing with men for funding, equipment and students was something else entirely. Blazing that trail couldn’t have been easy.”

At one point McMaster had a plaque honouring Gaiser. It was moved to a garden, which in turn has made way for the new Teaching and Research Greenhouse.

“Honouring Dr. Gaiser is one way McMaster can support its aspiration for inclusive excellence,” says Llewellyn, who is glad to hear the university is looking into ways to once again recognize Gaiser.

“How we honour our past shows what we value today and aspire to become in the future.” — Kristina Llewellyn, historian

An outstanding mentor

Gaiser is the reason McMaster built its first academic greenhouse: When the university relocated to Hamilton in 1930, Gaiser refused to make the move unless there was a greenhouse to support her teaching and research.

In fact, Gaiser spoke up — often in support of women — long before she became a tenured professor in 1937: She pushed for women to be allowed to study in the university library on Saturday afternoons. She wanted the university to hire more women faculty members. She called for the university to appoint a Dean of Women — and in 1930, McMaster did.

Gaiser was known to be a demanding professor who held her students to high academic standards. In 1926, she wrote to the chancellor that outside speakers should replace class parties.

“There’s a greater need for training our students rather than for little social parties only.”

— Lulu Gaiser to the chancellor, in 1926

It paid off for her students. At least seven earned PhDs at American universities.

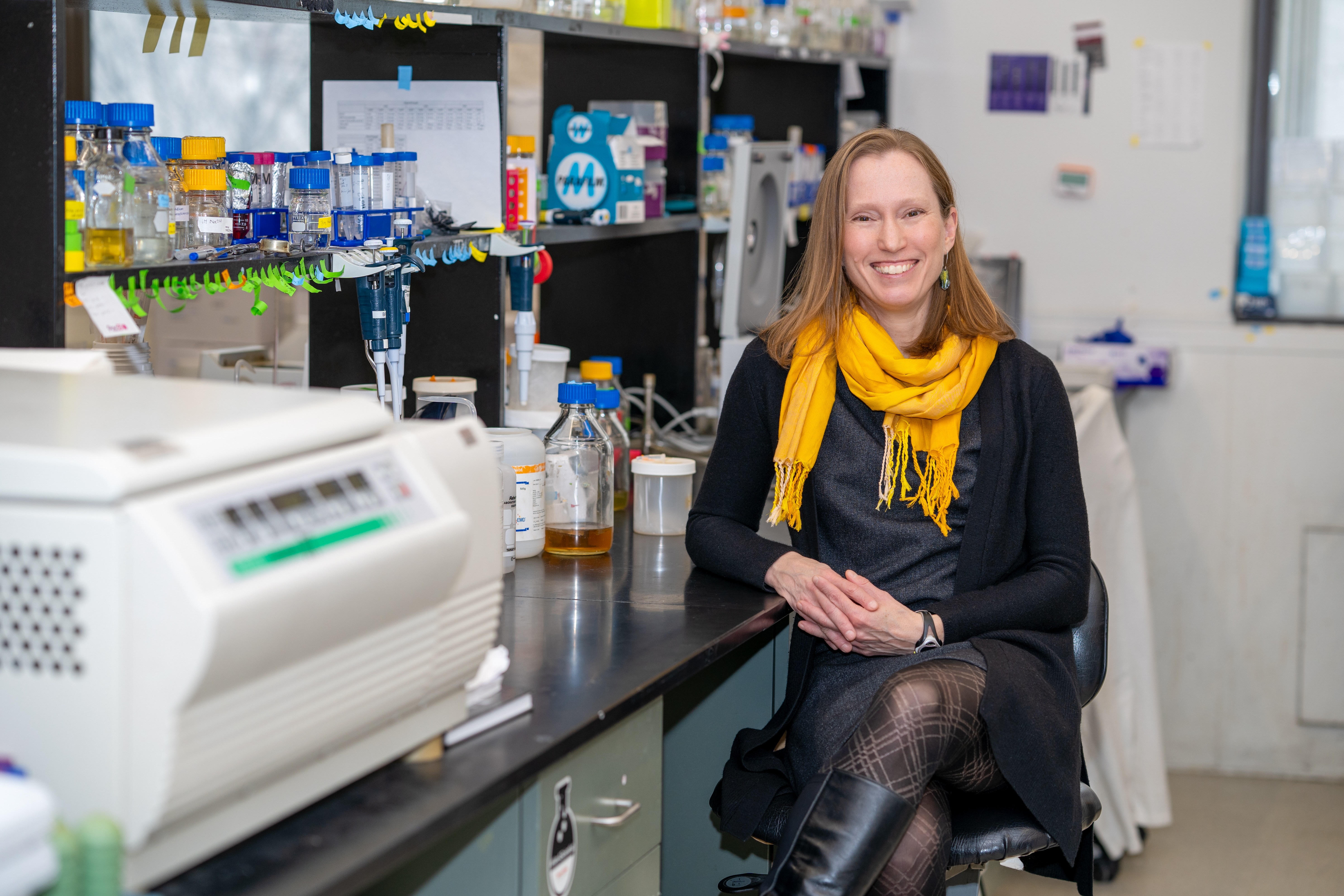

And Gaiser trained an entire generation of Canadian botanists, says biology professor Elizabeth Weretilnyk.

“In the early days of the National Herbarium of Canada, all of the key people were likely trained by Lulu,” Weretilnyk says.

“From everything I’ve read, Lulu was an outstanding supervisor and mentor.” — Elizabeth Weretilnyk, biologist

One of Gaiser’s standout students was William Cody. Considered the “doyen of Canadian botanists,” Cody graduated from McMaster in 1946 and was awarded an honorary doctorate in 2007.

Another student she supervised — Harold Senn — recommended an area near McMaster as a future botanical garden.

Gaiser was “influential in the first field botany project at the Royal Botanical Gardens,” RBG Director of Science David Galbraith wrote in a 2024 tribute.

The arrival of a strong woman

Like many women pushing traditional boundaries at the time, Gaiser didn’t receive the most collegial welcome.

In his book about documenting 100 years of the biology department, Stanley Bayley wrote that Gaiser was called the first invasion of McMaster’s faculty by a woman, difficult and prickly, a rabid and vociferous feminist.

“Gaiser arrived like a breath of fresh air – in the prime of life, energetic, enthusiastic — and demanding,” wrote Bayley.

“Such attributes would be hard for many elderly men to take, especially coming from the first woman to join the faculty and in an age and atmosphere where male chauvinism prevailed.”

This does not surprise Renee Twyford.

“Smart and strong woman don’t always sit well with some men,” says the biology student, who had similar experiences before coming to McMaster.

Twyford, who graduates this spring with an honours degree in biology, started volunteering at the greenhouse in her second year and has been there ever since.

“I would’ve had a great time learning from Dr. Gaiser. She reminds me of all the wonderful women I’ve had as professors.”

— Renee Twyford, biology student

Gaiser was challenged by zoology professor Emerson Warren. Hired a few years after her, Warren started complaining about her to Chancellor George Gilmour.

Gaiser had more student assistants in her labs, he said, forcing him to rely on less experienced sophomores.

“The same mill that grinds out good botanists seems to supress the development of good zoologists,” he wrote.

Warren’s lobbying paid off: In 1942, Gilmour split the biology department, appointing Warren head of zoology; Gaiser head of botany.

“When the department was divided, Chancellor Gilmour had no choice but to appoint Gaiser head of botany although she could not have been an easy person for him to deal with,” wrote Bayley.

After Gaiser turned down an offer from Harvard’s Weaton College, Gilmour wrote to the National Research Council of Canada and Columbia University.

According to Bayley, Gilmour wrote to his counterpart at Columbia, “the problem of us [is] that the University is not primarily a research institution and Miss Gaiser seems not to be best fitted for undergraduate teaching. I am coming to feel she will find her greatest happiness and usefulness if a research post can be found for her.”

Gilmour eventually created a research post for Gaiser at McMaster, appointing her the senior professor of botanical research.

At Gilmour’s recommendation, Norman Radforth — a former part-time assistant professor who’d once worked for Gaiser — became the head of botany, dually appointed as the founding director of the Royal Botanical Gardens.

Three years later, Gaiser requested a year’s leave of absence with early retirement from McMaster at the end of August 1949.

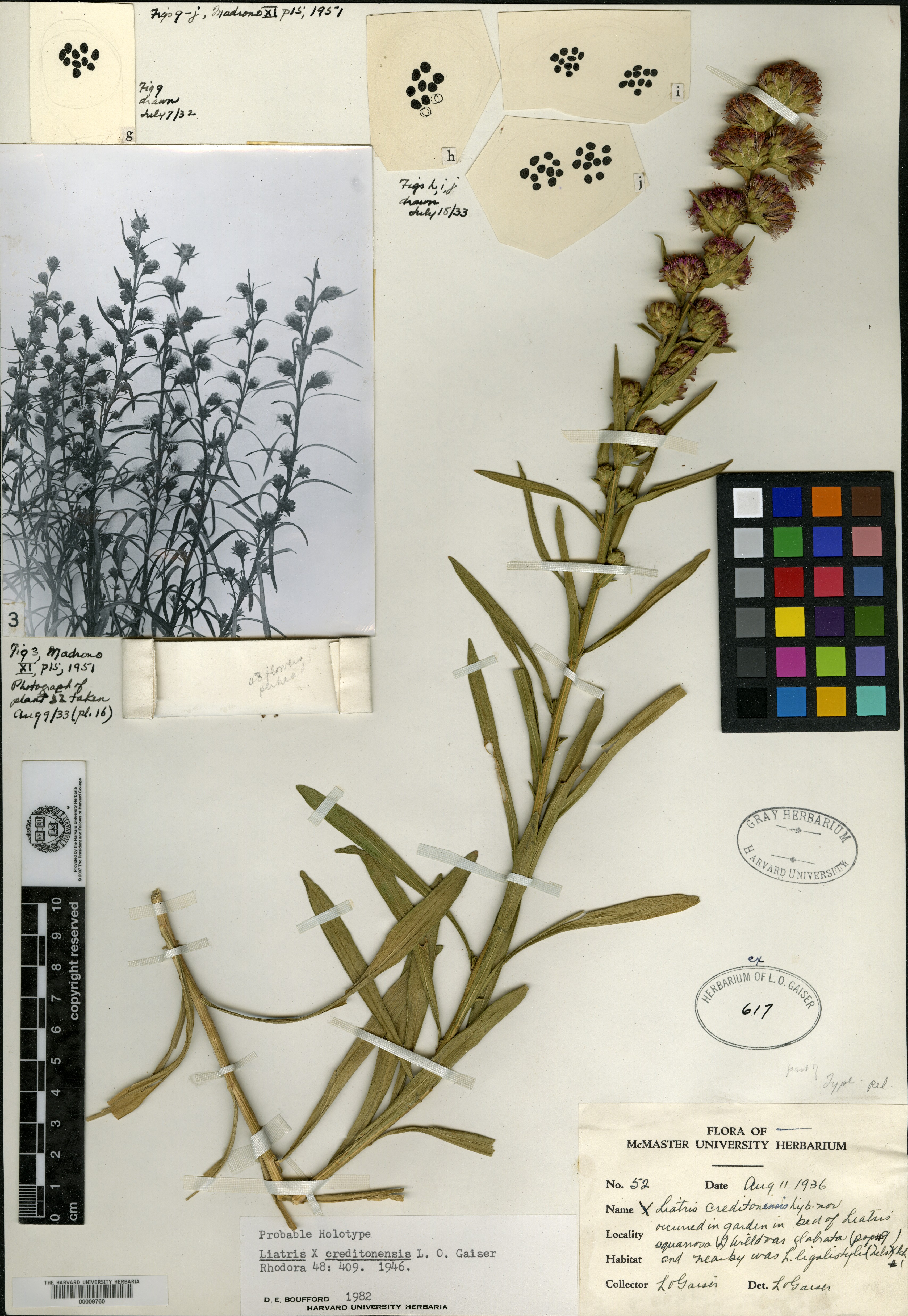

For five years after that, she worked at the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University. In 1954, she retired from academia to care for her widowed father full-time.

I get the sense Dr. Gaiser was no less bold, decisive, driven and direct as the men she worked with and reported to. She didn’t seem to suffer fools gladly. And maybe that approach ran against the stereotype where, as a woman, she was expected to be nurturing and mothering, collaborative and consultative not just with students but with the grown men who were her colleagues.”

— Marie Elliot, Chair of Biology

‘Imagine what she could’ve achieved’

Much has changed since Gaiser made history at McMaster as the first female faculty member.

In 2023, there were 439 women in full-time faculty positions across the university. In the department of Biology, there’s an equal number of women and men in full-time faculty positions.

In 1925, a third of McMaster’s students were women and few took science courses. Today, two-thirds of the undergraduates in the Faculty of Science identify as women. Across the university, women account for 55 per cent of McMaster’s 37,592 undergraduate and graduate students.

Women also hold key leadership roles. On July 1, Provost and Vice-President (Academic) Susan Tighe becomes McMaster’s ninth president and vice-chancellor.

The deans in the faculties of Science, Engineering and Humanities are women. In the Faculty of Science, three of the four associate deans are women.

Maureen MacDonald, the first female dean in the Faculty of Science, makes a point of telling students and colleagues that she won’t be the last.

And she almost didn’t apply for the job.

“I wasn’t willing to make my family a lower priority. I couldn’t spend nights and weekends working when my three kids needed me at home.”

When David Wilkinson, the provost at the time, heard that qualified women weren’t applying, he realized the job description had to change.

“David said the problem wasn’t with my commitments — the problem was entirely with the job.”

MacDonald eventually applied and was chosen after an international search.

Early in her tenure as dean, MacDonald introduced a life events support program in the Faculty of Science, covering the cost of hiring a postdoctoral fellow when a faculty member needs to step away from their research group.

It’s not lost on MacDonald that Gaiser didn’t have an ally like Wilkinson.

And Gaiser had none of the resources now in place to support women in leadership roles, from coaching and mentorship to professional and personal networking to training and development programs.

“Based on everything I’ve learned about Dr. Gaiser, she was a truly remarkable educator, researcher and administrator,” MacDonald says.

“Imagine what she could have achieved if any of these supports had been in place? If she had allies standing with her and advocating for her when she wasn’t in the room? Would she have spent the rest of her career at McMaster? Could she have been a key contributor when it came to building our university into a research powerhouse?”

It’s not just institutions that have changed for the better, says MacDonald, who sees how students work together in her research group and on student government, clubs and committees.

The students treat one another with genuine respect. No one’s questioning or challenging anyone’s ability to lead based on their gender. This is one more area where students are ahead of us and showing the way forward.”

—Maureen MacDonald, Dean, Faculty of Science

There are a few holdouts who’ve yet to come to grips with women in leadership roles, she says. They question women’s competence and test their authority in ways they’d never try with men in similar roles.

“Their numbers are dwindling fast but it only takes one to ruin your entire day.”

How to respond to someone like that is decision of its own, the dean says.

“You hope that feedback gets received in the spirit it’s intended and they’ll change their ways,” she says.

“But you always worry that you’ll be accused of overreacting, being dramatic and rude and then the conflict escalates. No leader has the time or energy to deal with that.”

Notably, MacDonald has yet to offer that feedback to any student.

“They’re our next generation of leaders. And from everything I’ve seen, we’re in very good hands.”

‘Still some work to do’

Professor Marie Elliot, who joined the biology department 20 years ago, is one of the handful of people at McMaster who knows all about Gaiser.

And she gained a greater appreciation for her after being appointed department chair in 2018.

With 900 undergraduate and graduate students, Elliot says she has much more support than Gaiser ever received.

An outstanding team supports the day-to-day work of the department, says Elliot. There’s a spirit of collegiality among faculty and staff.

“I can’t imagine what it must have been like for Dr. Gaiser to be an administrator with little to no support. She spent five of those nine years as an acting head of the biology department. I wouldn’t have lasted six months in those conditions.”

Elliot also wonders whether Gaiser was frustrated at how little time she had for research, her lifelong passion. Studying plants was something she did before, during and long after her time at McMaster.

At a recent meeting of biology chairs from across Canada, 25 of the 32 chairs were men — an imbalance that didn’t go unnoticed. “We have still have some work to do on that front,” Elliot notes.

At the meeting, they reviewed the results of a national survey of more than 200 biologists working in academia. A key stat jumped out for Elliot: Men spend 41 per cent of their time on research, 38 per cent on teaching and 20 per cent on service. Women spend 49 per cent of their time on teaching, 30 per cent on research and 21 per cent on service.

“Dr. Gaiser was reminded time and again that teaching was her primary responsibility, and her administrative responsibilities would’ve left little time for research.”

The double bind

“It’s interesting that history sees Gaiser as ‘prickly and difficult’ and that she was treated as such by colleagues and leaders at the time,” says Erin Reid, the Canada Research Chair in Work, Careers and Organizations, and a professor of Human Resources and Management in the DeGroote School of Business.

“She doesn’t necessarily sound more difficult than her colleagues.”

Research on women’s careers in traditionally male workplaces — such as universities — shows that gender stereotypes shape how people’s behaviour is interpreted and responded to by those around them.

Gaiser likely faced a “double-bind,” says Reid.

“To succeed in her academic role, she would have needed to behave assertively and aggressively and yet she was still likely expected by others to behave in ways that fulfilled feminine stereotypes: Behaviour that might’ve been interpreted as appropriate for men could’ve been coded as ‘difficult and prickly’ for her.”

Full-time professional, primary caregiver

Gaiser became her father’s primary caregiver when her mother died in 1936, a year before she was promoted to full professor and made acting head of McMaster’s biology department. He continued to live in Huron County.

“I’m not sure how Dr. Gaiser managed it all,” says Faculty of Science researcher Allison Williams, a social and health geographer who leads a groundbreaking international project to develop carer-friendly workplaces that support employees caring for older adults.

Caring for older family members is a responsibility that continues to fall primarily on women, something that hasn’t changed significantly since Gaiser left Harvard and her career to care for her father full-time.

“We’ve been working so hard for how many years to gain gender equality at work and it’s all taken away because women are expected to provide unpaid care to adult family members?”

— Allison Williams, health geographer

“I do conclusively know from all of the research that being a primary caregiver to a family member for an extended period of time without support can lead to serious physical and psychological strain, exhaustion, chronic stress and burnout.”

Ahead by a century

After leaving Harvard, Gaiser no longer had a greenhouse or herbarium, but that didn’t stop her from being a researcher.

In 1957, with funding from the Ontario Agricultural College and the American Philosophical Society, Gaiser began a floristic survey of neighbouring Lambton County.

Her fieldwork took her to Indigenous communities on the northern and southern shores of Lake Huron.

Gaiser enlisted the help of Indigenous women to identify and collect specimens at a time when researchers were known for showing up unannounced and leaving without sharing their findings or knowledge.

“Of course Lulu shared her knowledge with Indigenous women. She was an exceptional teacher and mentor to the end.”

— Elizabeth Weretilnyk, Professor, Biology

She was doing more than collecting specimens for future researchers: Gaiser was on a mission to save flora and fauna throughout Southwestern Ontario.

Gaiser foresaw the environmental damage to forests and fields caught in the path of urban sprawl.

“To one returning in the middle of the 20th century after a professional career in botany, it became obvious that full attention should be paid to the flora,” she wrote in the introduction to A Survey of the Vascular Plants of Lambton County, her final publication.

“The question is clear: what will happen to the plants?”

— Lulu Gaiser, in the introduction to her final publication

Gaiser died in her sleep on April 7, 1965, a year after her father’s death. She was 68 years old. Her book was published posthumously by the Canada Department of Agriculture.

MacDonald is ready to do her part to keep Gaiser’s legacy alive.

Discussions are underway to make sure Gaiser is forever recognized in a way that befits a trailblazer.

A pioneer of plant genetics

Lulu Gaiser did more than make history at McMaster University.

For her PhD thesis at Columbia University, Gaiser studied the chromosomes of Anthurium, a genus of about 1,000 species of flowering plants. The Royal Society published her thesis as a book in 1927, making it the first published work by a Canadian scientist on cytotaxonomy.

Cytotaxonomy, which uses the characteristics of cellular structures to classify organisms, was an emerging field of study in the 1920s, and Gaiser became an early adopter of using chromosome numbers to classify plants.

Within seven years of completing her thesis, Gaiser had published four extensive lists surveying the cytotaxonomic literature, earning her international acclaim.

That was a remarkable accomplishment for two reasons, says McMaster Biology professor Elizabeth Weretyilynk: The speed of her work, and her productivity as a scientist.

“Lulu Odell Gaiser was a pioneer in the field of cytotaxonomy for publishing much of the early organized lists of chromosome counts, helping develop the field of cytotaxonomy and training many students in cytotaxonomy.” — Plant Systematics World in Unsung Heroes of Botany, 2018.