Teaching awards? They’re probably somewhere under this huge trove of student tributes

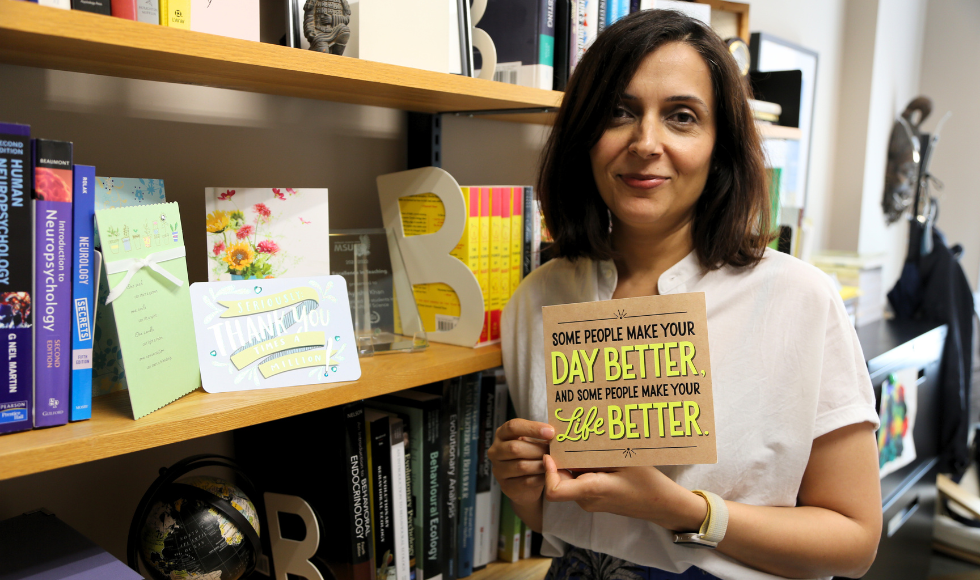

Ayesha Khan has been recognized more than once with teaching awards, but what she really values is the large — and growing — stash of hand-written, heartfelt notes from her students. (Photo by Jay Robb, Faculty of Science)

You won’t find Ayesha Khan’s three teaching awards displayed in her office.

Instead, you’ll come across an impressive collection of thank-you letters, notes and cards from students.

This trove of kind words is what happens when you’ve taught more than 15,000 undergrads and you’re very good at your job.

Just how good? In only 11 years here, the associate professor in the department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour has been recognized with the President’s Award for Outstanding Contributions to Teaching and Learning and two McMaster Students Union Teaching Awards, plus another pair of nominations.

In October, she’ll receive provincial honours, with an Award for Excellence in Education from the Ontario Conferation of University Faculty Associations.

Khan appreciates the awards, but values the messages from students above all else.

And these aren’t perfunctory “thanks for a great year” messages. These students are taking the time to hand-write heartfelt paragraphs that get into the specifics of how Khan helped shape the trajectory of their lives.

Genuine enthusiasm and the element of surprise

More than a few students have told Khan how important it was to have a professor who looks like them at the front of the class – Khan’s parents moved to Canada from Pakistan in the 1990s.

After graduating with a PhD in Behavioural Neuroendocrinology from Mac, Khan taught at the University of Toronto and Toronto Metropolitan University.

When a full-time teaching track position came up at Mac in 2013, she applied but didn’t think she had a shot. At best, applying would be a learning experience and a trial run for a job at another university, she figured.

When a McMaster number came up on her phone, she let it go to voicemail, thinking she’d listen to the bad news at the end of the day.

It was a job offer. “I was shocked.”

Khan knew from her time as a student that McMaster’s commitment to being research-focused and student-centred would give her the licence to test drive new and innovative approaches to teaching and learning.

She was among the first faculty members in the department to embrace community-based learning. That kind of collaboration comes with risks and factors beyond anyone’s control, and sometimes the best laid plans go awry.

In those moments, Khan says she is grateful to have always had the support of her department chairs.

Khan’s approach to teaching was heavily influenced by professor Denys deCantanzaro, her graduate supervisor, mentor and teaching muse.

“You only needed to watch Denys’ expressions during his lectures to know how enthusiastic he was to talk about his research,” she says.

“His genuine enthusiasm and excitement made you pay closer attention and want to learn.”

She tries to mirror that approach in her courses by constantly incorporating new content that she finds unexpected and exciting.

“I try to include an element of surprise whenever I can,” she says. “I want students to be asking what’s next and following along.

Continually “refreshing” lectures can be very labour-intensive, and it doesn’t always work out the way she had hoped, Khan says. “But it’s worth doing.”

Challenging, inspiring, always learning

She’s learned to take the same advice that she gives to students: You can’t be perfect at everything. Mistakes happen. Not every lecture will hit the mark. Be kind and show compassion to yourself.

Looking back on her 14 years of teaching, Khan says the biggest change and greatest challenge is helping distracted students stay focused during lectures.

Social media has wrecked attention spans and Khan admits she’s not immune herself. So she starts each class by asking students to come up with a plan for giving their undivided attention.

She also leads off her lectures by playing music to help quiet buzzing minds. Classical music seems to work, though Khan sometimes mixes in The Cure – the band that gave the world Disintegration and There Is No If somehow still makes her happy. (She played the decidedly more upbeat Friday I’m In Love closer to the end of term.)

Khan makes a point of showing students why the things they study are relevant: Where she once would’ve delved straight into neuroanatomy, she now starts by discussing how concussions, binge drinking, Alzheimer’s disease and HIV/AIDS affect the brain.

And she learns from the students as she teaches them. Over the years, she says the thing she is most amazed by is their remarkable resilience.

Two students stand out: One suffered an acquired brain injury after getting hit by a drunk driver, and the other went to classes during the week and spent every weekend with her mom at a hospice in Toronto.

Khan told both students it would okay to hit pause, but both were determined to continue.

Helping them persevere was an absolute privilege, she says. “They demonstrated such extreme resilience – it was incredibly inspiring and humbling.”

And it’s that resilience that helps put the occasional difficult day into perspective for Khan. And there’s always an office full of thank-you cards to reread.