From the Walrus: At McMaster University, building a better 2080 starts now

The Imagining 2080 forum invited future-thinkers from across generations and disciplines to envision possible futures for Canada.

This article is republished with permission from the Walrus Lab. Click here for the original.

If we want to build a better future by 2080, we need to start working on it now.

That was the key takeaway from “Imagining 2080: A Forum on Canada’s Futures” — a three-day conference focused on what Canada could look like in two generations and what we need to do to get there. Hosted by the Future of Canada Project at McMaster University, the forum ran November 1–3 in Hamilton, Ontario.

The 57- year difference between now and 2080 is the same as 1966 to today — before Pierre Trudeau became prime minister, before computers hit our desks and then our pockets, before Canada even had its own independent constitution.

“It doesn’t seem that long ago, but the folks making decisions back then built the structure of our country, and it’s massively different,” said Ann Elisabeth Samson, forum organizer and strategic advisor for the Future of Canada Project.

“If we want the world to be a certain way, it depends on our values and actions today.”

The three-day event included a mix of speakers, discussion groups, and experiential workshops that brought together academic researchers, change-makers, and innovators to map out a course to 2080. By thinking about a hopeful future while acknowledging the challenges of the present, forum delegates were meant to choose optimism and envision what life could be like beyond our immediate concerns.

“I was inspired by the one-on-one conversations,” said Cynthia Roberts Pérez, a forum delegate who works in the museum industry. “It’s a big aspiration, to have so many people from so many backgrounds get together and look at what’s next.”

Imagining 2080 was the culmination of three years of work on the Future of Canada Project. It was funded by former Bell Canada Enterprises Inc. chairman and McMaster University chancellor emeritus, Lynton “Red”

Wilson, in 2020 with the goal of better understanding the issues and opportunities facing Canada.

Many people think only of technological changes when they imagine the long-term future, such as flying cars, talking robots, etc. But the choice of 2080 allowed attendees to look beyond immediate challenges and broaden the horizon to changes in society, politics, and beyond, while always maintaining a focus on what’s needed to make it happen.

Larger themes like democratized, local forms of government that help renew civic engagement and focusing on well-being of individuals and society rather than economic growth were realized. Discussion groups focused on areas such as the future of our economy, entrepreneurship in Canada, the impacts of climate-related migration, and more.

Participants then brainstormed solutions to address concerns about how to replace jobs in an increasingly automated economy, new methods for collective control of our data online to increase security, and protection of Indigenous rights as new land opens up in Canada’s north.

“The first step in change is to actually have a sense of where you want to go,” said Peter Padbury, a delegate who recently retired as chief futurist at Policy Horizons Canada.

The forum also featured a symposium with a number of researchers—who received funding from the Future of Canada Project—covering topics in healthcare, Indigenous reconciliation, democratic resilience, and systemic racism.

Delegates could choose one of five field trips in and around Hamilton to places where they could glimpse the future, including the nuclear reactor at McMaster University’s central campus, a multi-million-dollar waterfront development and rejuvenation project led by the City of Hamilton, and a forest and nature reserve where McMaster scientists are studying atmospheric carbon dioxide and ways to mitigate climate change.

“All work in 2080 is climate work, whether it’s about adaptation, resilience, or infrastructure,” said Dylan Hendricks, a director at the Institute for the Future who attended the conference. “There’s going to be the need to build entirely new settlements, entirely new regions of this country. We need to proactively build a solid economy where people can have good lives doing that kind of work.”

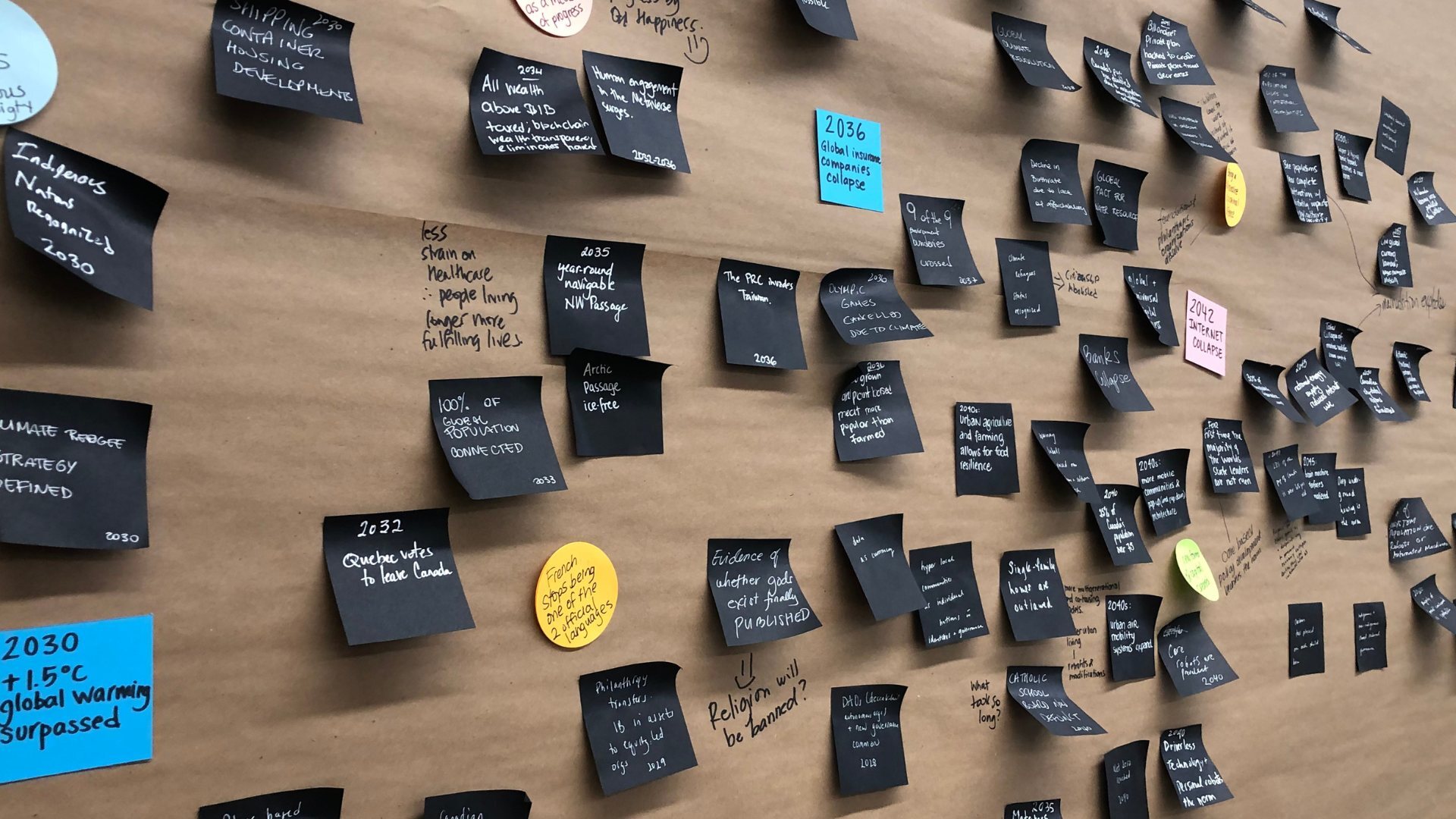

On the final day, participants were asked to define a desirable future for Canada, then work backward through each decade from 2080 to identify key milestones, recognize potential barriers, and identify the resources and structures needed to achieve the end goal. This technique, called backcasting, isn’t about predicting the future—it’s about creating a roadmap to shape it.

“It’s not just about interesting people having ideas, it’s also about how you influence policy, how you cultivate and nurture the next generation of leaders who will make this happen,” said Samantha Nutt, chair of the Future of Canada Project Council.

The council—a diverse group of forward-thinking leaders from across Canada—was brought together to shape the project by developing research themes and articulating a vision for Canada’s future. In addition to Nutt, who leads War Child Canada and has undergraduate and medical degrees from McMaster, the council includes prominent figures, such as former CBC anchor Peter Mansbridge, musician Chantal Kreviazuk, former politician Lloyd Axworthy, and Indigenous midwife and executive leader Sara Wolfe.

The forum itself was an innovative step for McMaster University to take, one that reflected Wilson’s desire for the work of the Future of Canada Project to connect the academy with the outside world across many disciplines. In 2022, Wilson followed his initial gift of $5 million in 2020 by donating $50 million for the establishment of a new school within the McMaster faculty of humanities and faculty of social sciences called the Wilson College of Leadership and Civic Engagement.

“We’re looking forward to continuing this work as we develop our programming for Wilson College,” said Pamela Swett, dean of McMaster’s faculty of humanities, addressing the final day of the forum.

“We know that long term future forward thinking is crucial for our civic and community leaders. McMaster is proud to be a place where these interesting conversations can happen.”

Incoming undergraduate students in fall 2025 will be the first cohort of a new degree in leadership and civic studies, the first of its kind in Canada. These students could still be working in 2080, making it all the more important to choose the world we want to live in now.

WHY 2080?

“Imagining 2080: A Forum on Canada’s Futures” looked beyond the next generation to encourage the imaginations of speakers and delegates. Choosing the year 2080 was a conscious effort by the organizers to expand the boundaries of debate.

“We hoped by challenging people to think longer term, everyone could start looking at things differently,” said Ann Elisabeth Samson, forum organizer and strategic advisor for the Future of Canada project. “You can move beyond the things we feel mired in today, that seem unsolvable, and focus on moving towards a more hopeful future.”

Fifty-seven years is a long time—long enough for seismic changes in demographics, technology, politics, and society. Businesses, governments, academics, and organizations that make future projections, such as the United Nations, are usually focused on the next ten to twenty years. But a longer timeline means our current assumptions about people, politics, and society can be reconsidered.

“It gets us out of the trap of tomorrow,” said Samantha Nutt, chair of the Future of Canada Project Council. “There are so many great unknowns in the equation that it forces you to think about what kind of society we want to build.”

This was originally published by the Walrus. Click here for the original.