“Not vain your sacrifice”

Photo by Sarah Janes

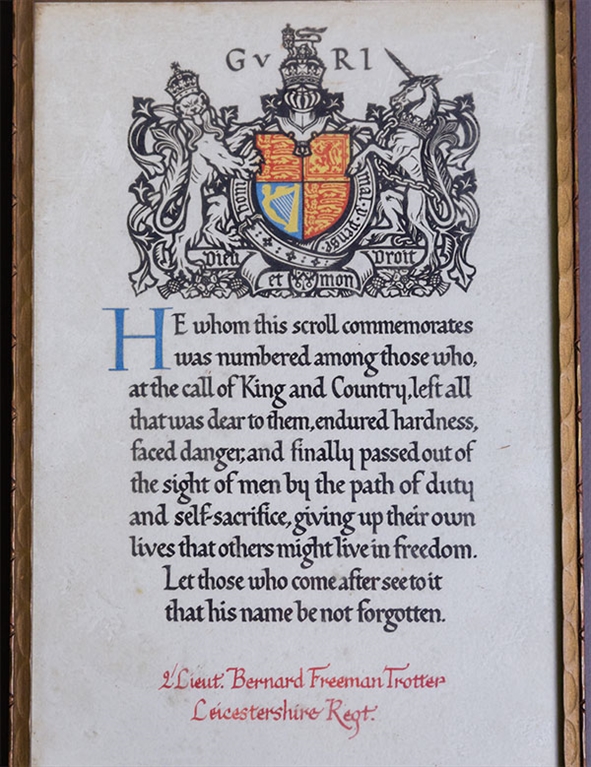

In April 21, 1917, Bernard Trotter class of 1915, wrote to his mother. She was back home in Toronto; he was near the battle lines in France, a transport officer for the British Army.

“Don’t know where I’ll be at next writing; but wherever it is, I’ll be after loving you every minute of the time and every foot of the way, as I do now. Till then, and forever,” the 26-year-old signed off, before squeezing in a cheerful P.S. explaining that he was attaching a “pome” about the war.

By the time Ellen Trotter opened that letter, her son was dead: one of 60,000 Canadians who went to war and never came back.

A hundred years after the end of the First World War, the poem he sent in his final letter stands out as his best-known work – a tribute from a soldier to his fallen comrades.

We shall grow old, and tainted with the rotten

Effluvia of the peace we fought to win,

The bright deeds of our youth will be forgotten,

Effaced by later failure, sloth or sin;

But you have conquered Time, and sleep forever

Like gods, with a white halo on your brows—

Your Souls our lode-stars, your death-crowned endeavour

The spur that holds the nations to their vows.

(Ici Repose, 1917)

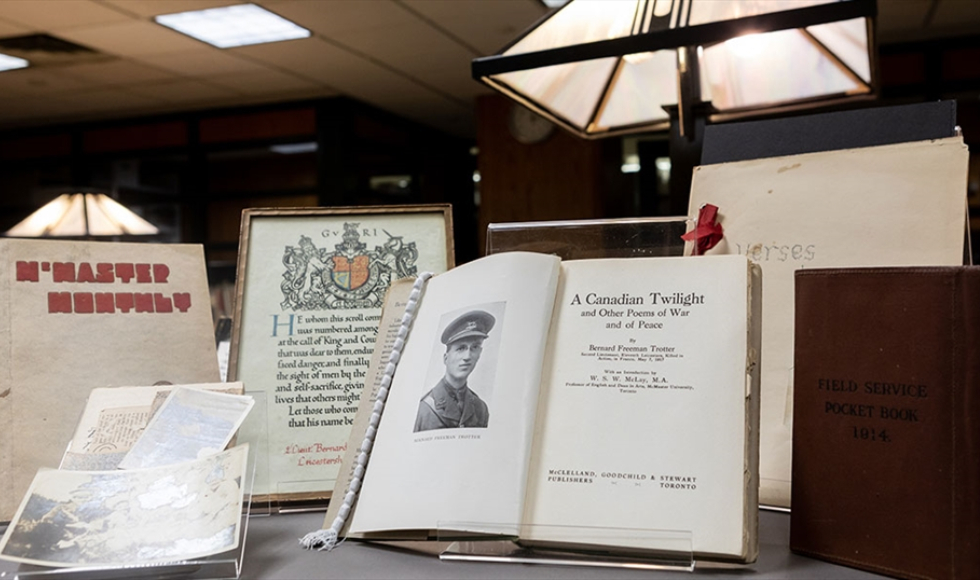

Almost a century later, Trotter’s family gave the University their immense trove of his poetry, essays, letters, notebooks and childhood writings, including the original poem and the letter that carried it.

While Trotter may not be as readily recognized today as John McCrae, the Canadian who wrote In Flanders Fields, his legacy is carefully tended by McMaster archivist Renu Barrett.

“He could have been like Robert Graves or Rupert Brooke,” says Barrett. “But he wanted to serve his country — so many young men did — and that took precedence.”

Growing up in Nova Scotia, Bernard Trotter kept diaries, composed poems and was a prolific letter writer. He was adept at finding silver linings — he wrote about how beautiful the clouds were when it rained out his fishing trip, and delighted in a clever comeback from his sister when he teased her.

By the time he was 15, Trotter was collecting his poetry into hand- bound volumes as gifts. Even as a teenager, his writing was evocative and surprisingly mature. But Trotter didn’t take himself too seriously: Mixed in among more solemn poems about nature or a son’s love for his saintly mother are cheerful ditties like My Dad an’ I, a jaunty, affectionate little rhyme about the hijinks he got up to with his father.

In his late teens, Trotter gained admission to McMaster University, but ill health forced him to abandon his plans and move out west to the warmth of California. His poems from those years don’t reflect his longing for home, or for his ambitions. Instead, he wrote about the mountains, the sea and the beauty that gave him a sense of peace at a discouraging time of his life.

I found a grotto in a nest of hills,

Half hidden by down-drooping branch and vine

Where year by year the mountain torrent drills

Deeper its pathway between slopes of pine

(The Violet’s Home, California, 1908)

When his health improved, Trotter returned and started his studies at McMaster in 1910.

His roots at Mac ran deep — his father had taught there as a young man and rejoined the University the same year as his son, to teach theology. Trotter’s siblings Reginald, Marjorie and Francis studied at McMaster as well. And after his death, his mother, Ellen, was dean of Wallingford Hall.

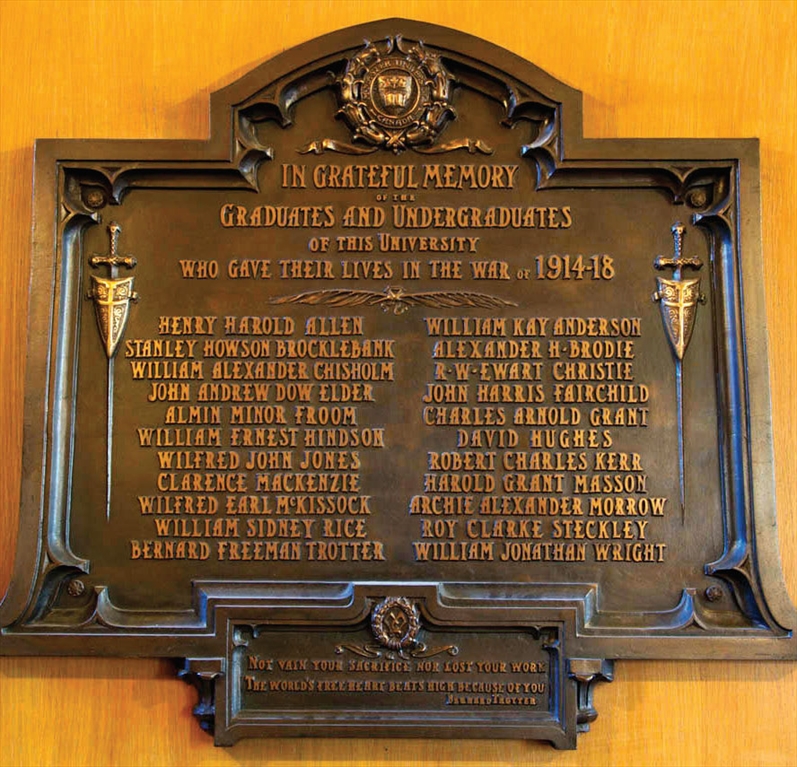

Those roots are evident still: Trotter’s name and a line from one his poems is on a plaque at Alumni Memorial Hall, honouring students and graduates who died in the war.

At McMaster, Trotter wrote constantly, filling notebook after notebook, and served as editor of the McMaster Monthly for a year. By the time he graduated with a BA, his poetry had been published in Harper’s magazine.

When the war started, Trotter wanted to serve his country, but the Canadian Army refused to send him overseas because of his record of frail health. He vented his frustration in a poem called A Canadian Twilight.

Like a caged leopard chafing at its bars

In ineffectual movement, this clogged spirit

Must pad its life out, an unwilling drone

In safety and in comfort; at the best

Achieving patience in the gods’ despite

And at the worst—somehow the debt is paid.

(A Canadian Twilight, 1915)

Undeterred, he continued to pursue the military, eventually enlisting in the British Army and being sent overseas in late 1916.

His gift for seeing the positive really came into its own once he joined the fighting in France. His letters home are cheerful and full of tales of his “luck,” — he was lucky in his lodgings; he was lucky to be a transport officer, not a combat soldier; he was lucky to have found a quiet moment in the mess tent to dash off a quick note to his sister. Above all, he considered himself lucky to be serving.

When Trotter’s mother broke the news of his death to his brother, she, too, mentioned his luck: “Bernard was killed in action last Monday,” she wrote. “He would have chosen that, I think, rather than being sick and invalided home, or taken prisoner, or worse than anything, horribly mutilated as so many poor fellows have been.”

She also sent him a copy of the verses from Trotter’s final poem. “They are heart-breakingly pathetic now, but I am so glad we have them.”

Not vain your sacrifice nor lost your work:

The World’s free heart beats high because of you!

(To the students of Liège, 1914)