What makes a planet, a planet?

A ninth planet? Astronomer Rob Cockcroft has heard it all before.

It’s not that the discovery of a new planet wouldn’t be exciting, the postdoctoral research fellow says – it’s just that the claim has been made many, many times before.

There have been lots of boys crying wolf, it seems, when it comes to the discovery of a new planet in our solar system.

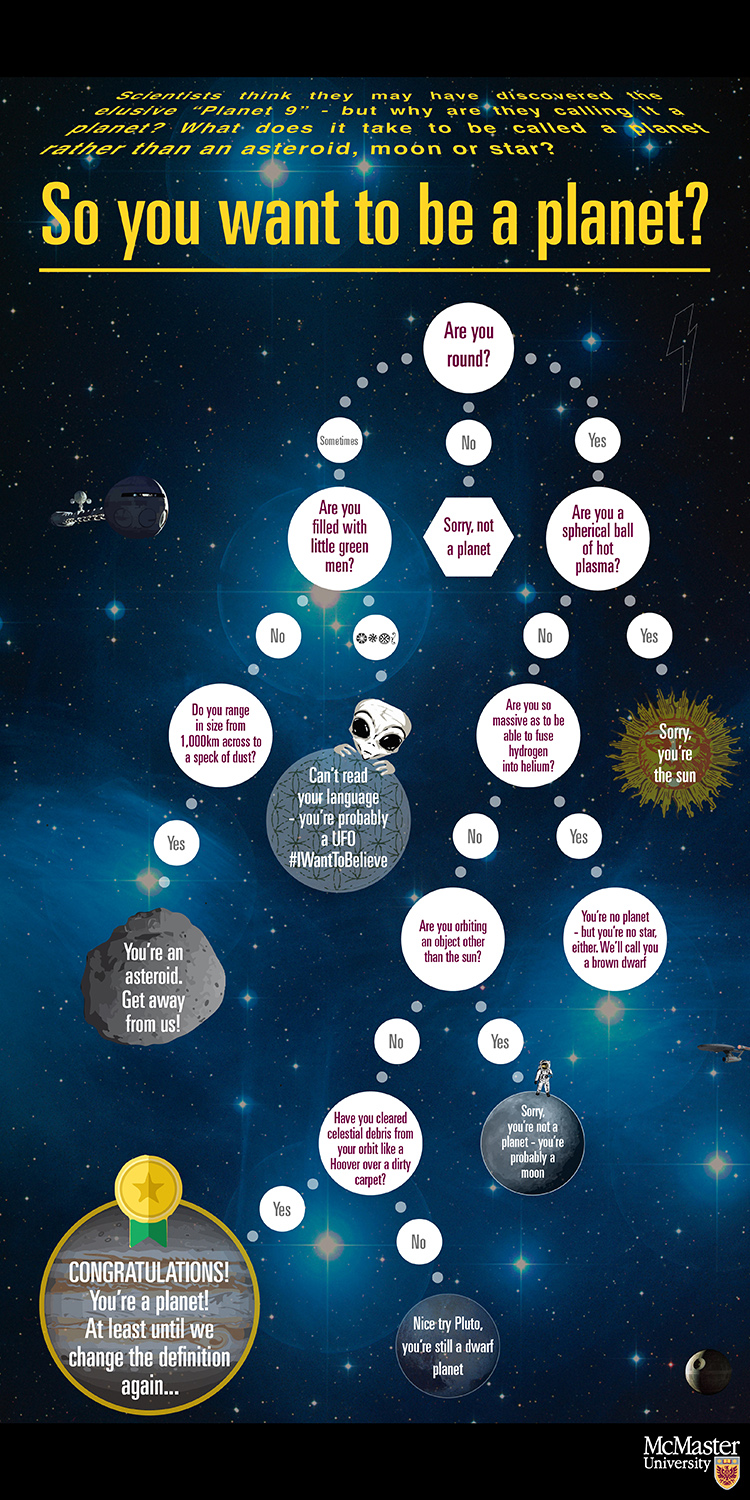

The discussion around the possible finding does raise a number of questions, however, about how celestial bodies are classified. What exactly would make this new body a planet? Why are some things called planets and others called brown dwarfs, large asteroids or other names? And why did Pluto lose its planetary status?

Cockcroft says the answer, like many things in the field of astronomy, is complicated.

He points to Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, as an example.

When Ceres was first discovered in 1801 it was classified as a planet. In the 1850s it was re-classified as an asteroid. Today, astronomers call it a dwarf planet – the same designation given to Pluto.

“Some people suggested that Pluto should never have been called a planet in the first place,” says Cockcroft. “And in 2006, it was re-classified as a dwarf planet when the criteria to be called a planet expanded.”

Cockcroft explains that to be considered a planet today, a celestial body in the Solar System must orbit the sun, be massive enough for its own gravity to make it round, and have cleared its orbit of smaller objects.

To sort it all out, Cockcroft helped us develop the flow chart below – which will surely be out of date the next time astronomers get together and argue about the status of another celestial body.