Partners share good chemistry as Health Canada grants pharmaceutical testing licence to McMaster labs

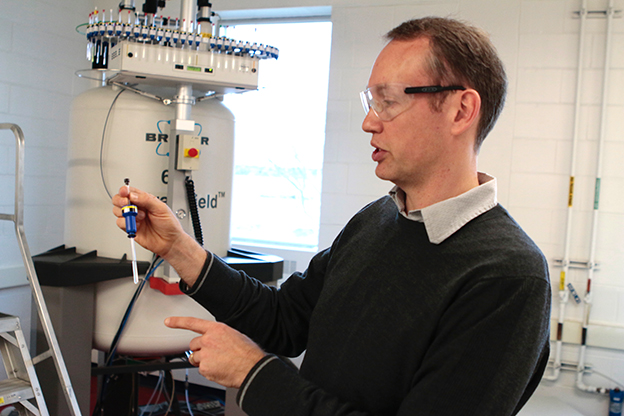

NMR application specialist Dan Sorensen with a drug sample. Health Canada has granted the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology the authority to test the active ingredients used in pharmaceutical products, making McMaster the first Canadian university to earn a drug establishment licence.

Health Canada has granted the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology the authority to test the active ingredients used in pharmaceutical products, making McMaster the first Canadian university to earn a drug establishment licence.

The designation is required to become part of the manufacturing chain for drugs and requires compliance with guidelines known as good manufacturing practices.

It’s a coup that will increase the depth and complexity of testing that staff members in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology already do for pharmaceutical companies and other businesses, and one that should multiply the revenue McMaster earns by doing such work.

“This is a remarkable achievement for an academic laboratory,” says William Leigh, Chair of Chemistry and Chemical Biology.

The licence means that staff research scientists in the department will be permitted to test the identity and purity of active pharmaceutical ingredients, using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and mass spectrometry.

“Health Canada recognizes that new, more thorough testing methods for active pharmaceutical ingredients are necessary,” says staff research scientist Hilary Jenkins. “We’re in a unique position to offer those services to the pharmaceutical industry, both because of our level of expertise as well as the advanced instrumentation at McMaster.”

The licence follows more than two years of work to establish the required systems and training, explains Leigh. He says the process succeeded because of the skills and knowledge of Chemistry research staff members who do the testing work alongside faculty members who are doing academic research and teaching.

Health Canada sets the bar high, because the new designation means that by doing such testing, qualified labs become part of the pharmaceutical manufacturing chain, where security and documentation requirements are extremely stringent.

If there is a problem with a finished drug, for example, investigators need to work back through the entire process, including testing, to see what went wrong.

“The data have to be absolutely immutable, absolutely secure,” Leigh says.

What the new designation means, Leigh explains, is that McMaster will now be able to ramp up the testing and problem-solving work it has been doing for pharmaceutical and other companies for more than 25 years.

Doing such work provides revenue to offset academic teaching and research costs, without diminishing the availability of the same equipment for the core academic mission.

It is entirely possible for academic and commissioned research to move forward in parallel, though it took careful planning and preparation to prepare for the new designation and the work that will flow from it.

“Aside from the time and effort required, it was a change process that challenged our mindset and forced us to learn new concepts and skills,” says NMR application specialist Dan Sorensen, who serves as the GMP quality manager. “Applied research in a regulated environment is quite different from the fundamental research that is traditionally performed at universities.”