McMaster grad shares his experience as a Ugandan refugee

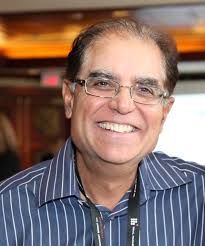

“There’s nowhere in the world like Canada,” says Amita Kanani, who fled Uganda in September 1972. A few months later, she met her future husband, Subodh Kanani (MD ’74), in Toronto. They know only too well the challenges Syrian refugees face. “But Canadians are very helpful to newcomers,” says Subodh.

January 25, 1971: Subodh Kanani was a 21-year-old medical student in Uganda, when Idi Amin seized power by military coup.

So began Amin’s ruthless eight-year rule over the former British colony, marked by political repression, corruption, human rights abuses, and ethnic persecution.

August 4, 1972: Amin ordered Ugandans of Asian descent to leave the country in 90 days. They could take one suitcase and no money.

Since Subodh was born in Uganda and over 21 years old, he couldn’t go to Britain with his parents as their dependent. Now a stateless refugee, he applied to the Canadian high commission in Kampala. He was granted landed immigrant status, one of 7,000 Ugandan refugees of Asian descent to be accepted by our country.

On the flight, he travelled with about 20 other medical students. When they landed in Montreal, they parted ways to their various destinations.

November 1, 1972: He arrived in Hamilton. “That’s when it really struck me,” Subodh recalls. “I’m alone. I don’t know anyone. I have $10 in my pocket!”

A few days later, it began to snow. “It was the first time I had ever seen my breath,” he says of the new-found cold. He had never seen snow either, of course. Fascinated, he rolled around in it and tasted it.

A series of fortunate events

Thanks to a helpful social worker, he registered for work as a lab technician. He also found a room to rent in a friendly Westdale home.

And he discovered that McMaster University had a medical faculty.

“Eight o’clock the next morning, I marched into the Dean’s office and asked if could see him.”  The Dean was not in, so Subodh waited. Several hours later, Dr. Fraser Mustard returned from Toronto, where he had been meeting with colleagues to discuss how to accommodate the influx of medical students from Uganda.

The Dean was not in, so Subodh waited. Several hours later, Dr. Fraser Mustard returned from Toronto, where he had been meeting with colleagues to discuss how to accommodate the influx of medical students from Uganda.

“Fortunately, I was his first Ugandan medical student,” says Subodh. He was accepted into the program and given funding of $3,000, half a grant, the other half a loan.

Subodh’s medical experience in Africa served him well – he had first-hand knowledge of tropical medicine, parasites and infectious diseases. He asked for a further year of study to learn more about first-world medicine. “It was a good decision. There was so much to learn.”

A warm coat and a fateful encounter

For the time being, though, the main thing on his mind was the cold. A friend suggested he take the bus to Toronto, where the Uganda Welcome House was providing warm clothing.

“I got a nice warm coat, and I was asked to sign the guest book,” he recalls. He flipped a page to see who else had signed it. “The first name I saw was Amita Nathwani.”

Amita and Subodh had been classmates in high school and then attended the same university. He jotted down her phone number from the guest book. They will celebrate their 42nd wedding anniversary this June.

Amita’s story is equally riveting. Her family lived 120 miles away while she studied science at Makerere University in Kampala. She graduated in March 1972 and was working at the Uganda Cancer Institute when Idi Amin issued his 90-day ultimatum.

Like Subodh, she was Ugandan-born and more than 21 years old. She too was rendered stateless. After her application was approved by Canada, Amita recalls the phone conversation with her parents: “Don’t wait for us, they said. You take the first flight out. And if we don’t see you now, we’ll see you whenever!”

A daring escape

As she waited in Kampala for the bus to take her to the airport, her parents arrived – thanks to one of their employees who had risked his own life to drive them. Together, they had quietly locked up the house and left at 2 a.m.

“I had five minutes to say goodbye,” recalls Amita, before her bus left. Her mother and younger siblings flew to Britain. Her father went to India.

On September 28, 1972, Amita was in the first group of Ugandan refugees to arrive in Canada. A younger brother was already pursuing studies in Toronto.

Amita held onto the last words her grandmother spoke to her: “You’re not leaving anything behind. You’re taking all that you have with you” – she meant Amita’s education, resourcefulness and intelligence. Her grandmother had also given Amita this useful piece of advice: “Take any job you can get.”

Amita did just that. “I started working on my eighth day in Canada and I’ve never stopped.” She soon resumed her career in cancer research, while Subodh established his family practice.

Far-flung family

They eventually reunited with far-flung family members, having stayed in touch by letter. Now with two grown children and three grandchildren, the couple is keenly aware of their good fortune. “It was almost overwhelming,” says Amita of the personal support she received when she first arrived in Canada.

Along with annual gifts to McMaster, the couple supports Aim for Seva, a charity that provides educational opportunities for schoolchildren in rural India.

They note that Syrian refugees will face additional challenges – dealing with language barriers as well as overcoming the trauma of a brutal and lengthy civil war. “But Canadians are very helpful to newcomers,” says Subodh.

Just as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau greeted the first planeload of Syrian refugees last fall, so too did Bryce Mackasey, Minister of Manpower and Immigration in the Pierre Trudeau government, greet Amita as she got off her plane in September 1972.

“We have since travelled the world, but nothing beats Canada,” says Amita. “What other country would offer you what Canada does?”