18th century science education “for women, by women”

This year’s McMaster-ASECS fellow, Anna K. Sagal examines a White Orchid Phalenopsis in the McMaster Biology Greenhouse, a flower specimen prominently featured in a number of rare 18th century botanical textbooks written by early female botanists. Sagal has been examining these textbooks, which are housed in McMaster University Library’s William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, for the past month.

BY Erica Balch

July 21, 2016

While examining a rare botanical textbook contained in McMaster’s William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, visiting scholar Anna K. Sagal made an unexpected discovery.

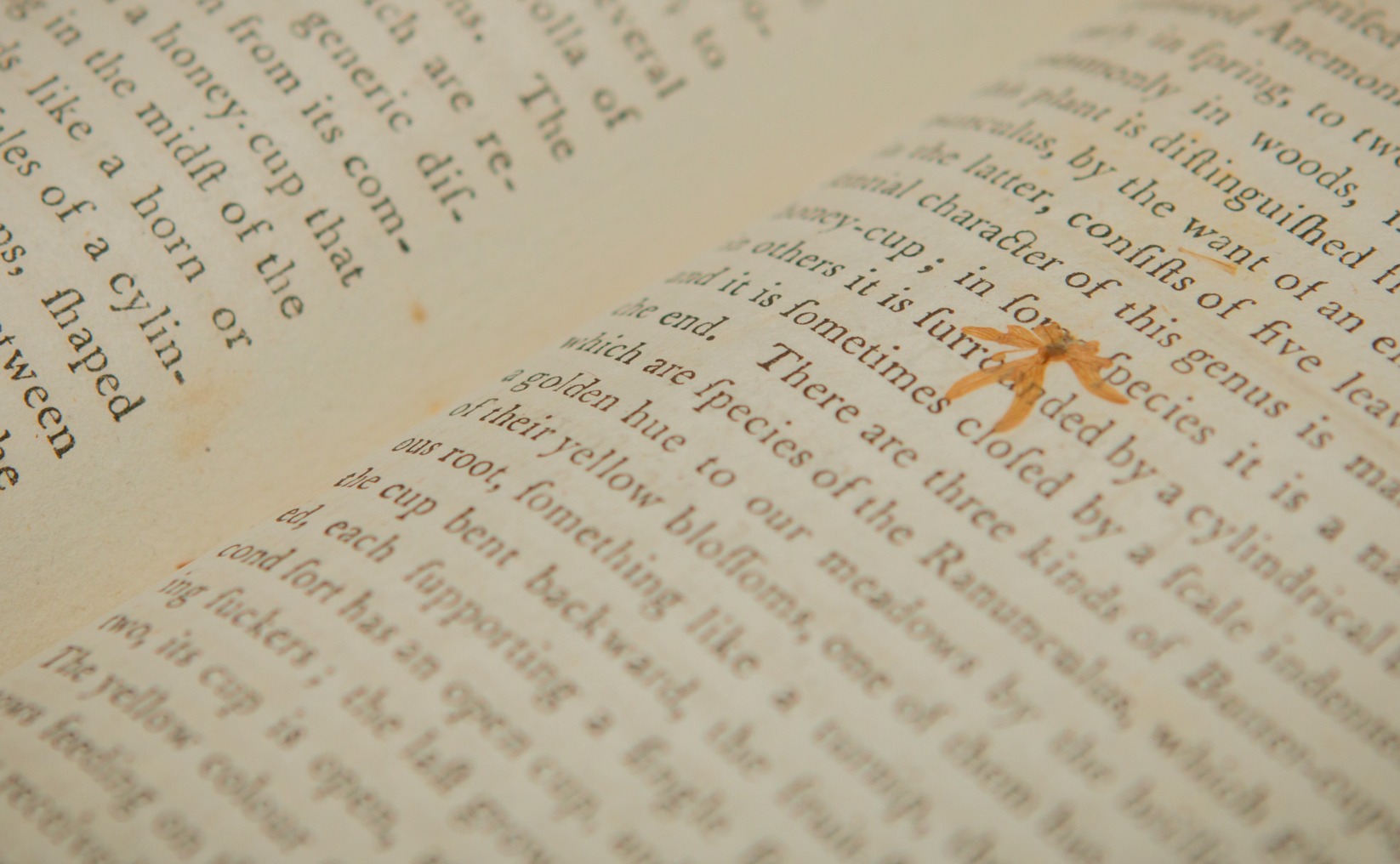

Pressed between the brittle pages of one of the textbooks written and used by early female botanists, she found a tiny golden flower, likely placed there more than 200 years ago– a tangible connection to the world of the 18th century and a symbol of women’s participation in one of the few fields of science open to them at the time– botany.

Sagal, who recently completed her PhD at Tufts University in Boston is this year’s recipient of the McMaster-ASECS fellowship,* a program that supports 18th century studies.

For the past month, Sagal has been poring over McMaster’s unique collection of 18th century English botanical textbooks, examining a number of works written and referenced by trailblazing women, early pioneers of female science education.

“This is science education for women by women,” says Sagal, “I’m interested in the role that scientific writing plays for women’s intellectual lives in a culture where women and science were often divorced from each other.”

According to Sagal, in the late 18th century, while many fields of science were still largely closed to women, botany was considered a “feminized science,” making it socially acceptable for women- who were culturally linked with nature and flowers- to participate in the practice of botany.

Unlike other fields of science like chemistry or astronomy, Sagal says botany was also comparatively accessible to women, requiring only simple, inexpensive equipment– like a magnifying glass– and access to a garden.

A number of female writers emerged at this time, publishing botanical textbooks aimed primarily at a feminine audience, but which turned out to have broader appeal.

“This is a rare moment when all of a sudden it’s OK for women to be publishing on this subject,” says Sagal. “You get male authors recommending these books and praising these female authors. These books also sold really well, they all went into multiple editions.”

Sagal says these textbooks, many of which are contained in McMaster’s collection, were quite different from works authored by men at the time. While they were scientifically accurate and contained the Latin terms associated with the Linnaean system of plant classification, they were written in a simplified, conversational style– sometimes taking the form of letters or dialogues– so they could be easily understood by female readers, many of whom didn’t know Latin.

And to keep costs low, they used fewer illustrations; instead providing detailed descriptions and encouraging aspiring botanists to take the textbooks into the field to identify plants and collect specimens, like the one discovered by Sagal.

Despite the popularity of these textbooks, she says many female authors nonetheless encountered strong cultural disapproval.

“These textbooks were being published by more liberal publishers– there was still broad social resistance to this,” she says. “There was an interesting tension at the time as to whether women were compromising their femininity by being too engaged with botany on a technical level. It took a lot of courage for these women to get these books published and then stand by their work as an intellectual authority.”

Sagal’s research at McMaster is contributing to her larger body of scholarship on women in scientific writing in the 18th century and the different genres in which scientific writing appears.

McMaster University Librarian Vivian Lewis says she’s pleased the collection is helping to support scholarly research like Sagal’s.

“The collection contains a diverse array of texts and materials that provide valuable insights into many aspects of life in the 18th century,” says Lewis. “It’s very gratifying that as this year’s McMaster-ASECS fellow, Anna has been able to make use of this unique collection to shed light on the some of the central social and cultural themes of the period.”

The materials consulted by Sagal include The Botanical Magazine, or Flower-Garden displayed (1787-1798), Botanical Dialogues (1797) by Maria Jackson, The British Garden (1799), by Charlotte Murray, and An Introduction to Botany (1796) by Priscilla Wakefield.

*The McMaster-ASECS fellowship is a month-long program administered annually by McMaster University Library and funded by McMaster’s Faculty of Humanities and the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies (ASECS).